Antoni Gaudi – Famous Spanish Architects

by David Fox

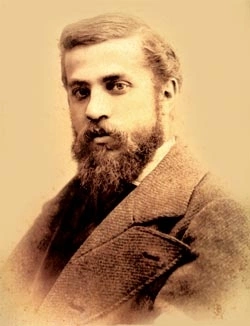

Antoni Gaudí, a Catalan architect, has become internationally recognized as one of the most prodigious experts in architecture, as well as the one of the top exponents of modernism.

Hard To Classify

His exceptional ground-breaking genius made him the inventor of a unique and personal architectural language that defies classification. The work of Gaudí is remarkable for its range of forms, textures, polychromy and for the free, expressive way in which these elements of his art seem to be composed.

The complex geometries of a Gaudí building so coincide with its architectural structure that the whole, including its surface, gives the appearance of being a natural object in complete conformity with nature’s laws.

Such a sense of total unity also informed the life of Gaudí: his personal and professional lives were one, and he collected comments about the art of building are essentially aphorisms about the art of living.

He was totally dedicated to architecture, which for him was a totality of many arts.

Here’s a good and quick intro video to some of Gaudí’s work in Barcelona. From this, you will surely see what makes him so special and one of the most famous Spanish architects ever.

Boilermaker

Antoni Gaudí I Cornet was born on June, 25, 1852, in Reus, provincial Catalonia on the Mediterranean coast of Spain, according to some biographers, although other claim that he was born in Riudoms, a small village near Reus, where the Gaudí family spent their summers.

He came from a family of boilermakers; due to this fact, a young Gaudí acquired a special skill for working with space and volume, as he helped his grandfather and his father in the family workshop.

His talent for designing spaces and transforming materials grew and prospered until it eventually metamorphosed into a veritable genius for three-dimensional creation.

Showing an early interest in architecture, in 18769/70 he moved to Barcelona, to pursue his academic career in architecture. In that time, Barcelona was Spain’s most modern city, as well as the political and intellectual centre of Catalonia.

His studies have been interrupted by intermittent activities and military service; accordingly, he did not graduate until eight years later. Gaudí was inconsistent student, but he was already showing some evidence of brilliance that opened many traces for him, allowing him to collaborate with some of his professors.

Chance Encounter

When Gaudí completed his studies at the School of Architecture in 1878, it was clear that the young architect’s ideas were not a mere repetition of things that had already been done up at that time, nor could anybody receive them with indifference.

Having obtained his degree, Gaudí settled down in offices in Calle del Cal in Barcelona. From his office and with a great dedication, he embarked on his architectural legacy, a large part of which is classified as World Heritage.

Towards the middle of 1878, it was a meeting that would lead to one of the most productive friendships, patronage relationships and cooperation that the world has known⎯ the chance caused the artist to cross paths with Eusebi Güell, a man who was a driving force behind Spanish national industry with a highly developed taste for arts.

From that point onwards, their productive cooperation was not merely the relationship between the client and architect; it led to a rapport based on mutual admiration and shared interests, building a friendship that gave Gaudí the opportunity to begin a rich professional career in order to develop all of his artistic aspirations.

Above and beyond his relationship with Güell, Gaudí received many commissions and proposed numerous projects; many of them were realized, but unfortunately, some never made it off paper.

Patterns Of Nature

Antoni Gaudí found the essence and the meaning of architecture by following the very patterns of nature and always respecting its laws. He did not copy the nature, but rather traced its course through a process of cooperation, and in that context he created the most beautiful and effective work through architecture.

On emergence from the Provincial School of Architecture in Barcelona in 1878, he practiced a rather florid Victorianism (that had been evident in his school projects), but very soon he developed a manner of composing by means of unprecedented juxtapositions of geometric masses, the surfaces of which were highly animated with patterned brick or stone, gay ceramic tiles and reptilian or floral metalwork.

The general effect is called Moorish, or Mudéjar, as Spain’s special mixture of Christian and Muslim design. Some of his the most interesting and remarkable examples of Mudéjar style are the Casa Vicens, from1878-80, El Capricho, from 1883-85, and Güell Estate and Güell Palace of the later 1880s, all located in Barcelona, except El Capricho.

He experimented with the dynamic possibilities of historic style: the Gothic in the Episcopal Palace, Astorga, 1887-93, and the Casa de los Botines, León, 1892-1894, and the Baroque in the Casa Calvet at Barcelona, 1898-1904; after 1902, his design elude more conventional stylistic nomenclature.

As A Tree Stands

Gaudí’s buildings became essentially representation of their structure and materials, except for certain overt symbols of nature or religion. In Villa Bell Esguard, 1900-02, and the Güell Park, 1900-14, in Barcelona, and in the Colonia Güell Church, 1898-1915, he arrived in a type of structure that has come to be called equilibrated; a structure designed to stand on its own without internal bracing, external buttressing, just ‘’as a tree stands’’.

Among the primary elements of his system were columns and piers that tilt to transmit diagonal thrusts, and thin-shell, laminated tile vaults that exert very little thrust. Gaudí applied this equilibrated system to two multistoried Barcelona apartment buildings: the Casa Batlló, 1904-06, a renovation incorporated new equilibrated elements, notably façade; and the Casa Milá, 1905-10, the several floors of which are structured like clusters of tile lily pads with steel-beam veins.

As was so often in his practice, he designed the two buildings, in their shapes and surfaces, as metaphors of the mountainous and maritime Catalonia’s character.

As an eccentric architect and as an admired, Gaudí was a significant participant in the Renaixensa, an artistic revival of the arts and crafts combined with a political revival in the form of fervent anti-Castilian ‘’Catalanism’’.

Both movements sought to reinvigorate the way of life in Catalonia that had long been suppressed by the Castilian-dominated and Madrid- centred government in Spain.

The main religious symbol of the Renaixensa in Barcelona was La Sagrada Família, the Church of the Holly Family, a project that was to occupy Gaudí throughout his entire career.

In the early 1883, he was commissioned to build this church, but he did not live enough to see it finished. Working on it, he was increasingly pious; after 1910, he abandoned virtually all other work and even secluded himself on its site and resided in its workshop.

The plans had been drawn up earlier, and construction had already begun, but Gaudí completely changed the design, stamping it with his own distinctive style.

In his drawings and models for the Sagrada Família, Gaudí equilibrated the cathedral-Gothic style beyond recognition into a complexly symbolic forest of helicoidal piers, hyperboloid vaults ad sidewalls; a hyperbolic paraboloid roof that boggle the mind and outdo the bizarre concrete shells built throughout the world in the 1960s by engineers and architects inspired by Antoni Gaudí.

After Gaudí’s death, work continued on the Sagrada Família. In 2010, the uncompleted church was consecrated as a basilica by Pope Benedict XVI.

Farewell

The magnificence of Antoni Gaudí’s architecture coincided, as the result of a personal decision by the architect, with a progressive withdrawal by the man himself. Gaudí, who in his youth had frequented theatres, concerts and tertulias ( social gatherings), went from being a young dandy with gourmet tastes to neglecting his personal appearance, eating frugally, and distancing himself from social life, while simultaneously devoting himself even more fervently to a mystical and religious sentiment.

Gaudí died on the 10th of June, 1926, after being knocked down by a tram while making his way, as he did every evening to the Sagrada Família from the Church of Sant Felip Neri.

After being struck, he lost consciousness, and nobody suspected that this disheveled 74 old man who was not carrying any identity documents, was the famous architect. He was taken to the Santa Cruz Hospital, where he was later recognized by the priest of the Sagrada Família.

Two days later, Gaudí was buried in that vary church, following a funeral attended by throngs of people; most of the citizens of Barcelona came out to bid a final farewell to the most universal architect that the city had ever known.

Apart from this and a similar, often uncritical, admiration for Gaudí by Surrealist and Abstract Expressionist sculptors and painters, Gaudí’s influence was quite local, represented mainly by a few devotees of his equilibrated structure.

He was ignored during1920s and 1930s when the International Style was dominant architectural mode. By the 1960s, he came to be revered by professionals and laymen alike for the boundless and tenacious imagination that he used to attack each design challenge with which he was presented.

About David Fox

David Fox is an artist who created davidcharlesfox.com to talk about art and creativity. He loves to write, paint, and take pictures. David is also a big fan of spending time with his family and friends.

Leave a Reply

|

|

|

|

Now get FREE Gifts. Or latest Free phones here.

Disable Ad block to reveal all the secrets. Once done, hit a button below

|

|

|

|