Cindy Sherman – Essay On Her Famous Works

by David Fox

The work is what it is and hopefully it’s seen as feminist work, or feminist-advised work, but I’m not going to go around espousing theoretical bullshit about feminist stuff. – Cindy Sherman

A contemporary master of social photography, Cindy Sherman is a key figure of the Pictures Generation, a loose circle of the most influential and productive American Artists who came to artistic maturity and recognition during the early 1980s, a period notable for the rapid and widespread proliferation of mass media imagery.

For the most of her remarkable artistic career, she has been the face of postmodernism.

Early Life

Ms Sherman was born in January, 19, 1954, in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, as a youngest of the five children, and shortly after her birth, the family moved to Long Island where she spent her early childhood.

Her father was an engineer and her mother a reading teacher, but although her parents shared a general disinterest in the arts, Cindy chose to study art in college, and afterwards, studied at Buffalo, at the State University of New York, in the early 1970s.

In this period, from 1972 to 1976, she began as a painter in a super- realist art style in Buffalo. The 1970s was an eclectic era for painters working in the aftermath of Minimalism, and feeling as though ‘’there was nothing else to say’.

But very quickly after, she found herself frustrated by the certain limitations of the medium and shifted her attention to photography, toward the end of 1970s, in order to explore a wide range of common female social role or personas.

Owing to a widely influential art instructor, Barbara Jo Revelle, she was exposed to conceptual art and other progressive media and art movements.

As Sherman came of age in the art world, the prevailing visual mode was painting dominated by ‘bad boy’ expressionist and figurative painters like David Salle or Eric Fischl. Photography was still thought to fall below painting in the hierarchy of mediums, but it granted women artists a mode that was relatively free from the heavy, conservative and male- dominated history of the painted canvas.

Many of the women artists adopted the camera and ‘’there was a female solidarity’’

Untitled Film Stills

After graduation, Sherman moved to New York in order to pursue her artistic career. In 1977, in her downtown residential and loft studio she started taking a series of photographs, a project she would eventually refer to as the Untitled Film Stills.

This series, 1977-80, is considered an early cornerstone of postmodernism.

In Untitled Film Stills, Ms. Sherman embodies the character of ‘Everywoman’; the artist served as both photographer and subject, transforming herself into the guise of various female archetypes, re-fashioning herself repeatedly and played the film noir siren, the prostitute, the girly pin-up, the housewife and the noble damsel in distress, also the movie stars of an earlier generation: Monica Vitti, Brigitte Bardot and Sophia Loren.

For about three years, she was occupied by black-and-white series, so that by 1980, Sherman had exhausted a myriad of seemingly timeless clichés referring to the ‘feminine’. This photographs of women by woman quickly gained attraction within the feminist community. A theorist Laura Mulvey, in one of her essays, contextualized Sherman’s work within the prevailing feminist modes of thought at the time.

End Of An Era

When Ms. Sherman arrived on the scene, it marked ‘the end of the era in which the female body had become, if not quite unrepresentable, only representable if refracted through theory’. Rather than sidestepping, Sherman reacts and shifts the agenda; she recuperates a politics of the body that had been lost or neglected in the twists and turns of 70s feminism.

It is easy to see some of the way Sherman’s representations of women avoided the proclivities of the day. The high heels and the heavy makeups, as well as the bullet bras of the film stills, harken back to the 50s rather than the au naturel look favored in the 70s.

It is not just a range of feminine expressions that are shown but the process of the ‘feminine’, as an effect, something acted upon.

Posing And Pretence

Museum of Modern Arts announced, in 1996, that it had just acquired Sherman’s Untitled Film Still series, the curators knew they had laid claim to one of the most representative works of the early 1980s American movement of ‘simulationism’ and ‘appropriation’; both terms refer to American artists’ mimicking, in the first half of the 1980s, widely circulating images in the mass media or former art masterpieces, and critically reworking them to arouse a sense of unease in the viewer, indeed often suggesting that culture had become a game of theatrical posing and egoistic pretence.

In Untitled Film Still #21, from 1978, Sherman takes on the role of the small- town girl just happening upon the Big City. She is, at first, suspicious of the metropolitan shadows and lights, only to be eventually seduced by its attractions.

Untitled Film Stills was Sherman’s big artistic break which secured her position in the New York art scene.

Debate

In 1981, the Arforum’s editor Ingrid Sischy commissioned a series for the publication, and that Sherman’s work took hold of the feminist imagination. The artist planned to riff on the Playboy centerfold with a pair of horizontal photographs showing women in intimate states of repose.

But, the Sherman’s women were all clothed, unlike Playboy’s women though. These works were never printed in Artforum, and it was the first time Ingrid Sischy refused to print a commission. She worried that the series would be misunderstood by militant feminists since they looked ‘’a little too close’’ to the pinups in actual men’s magazines.

However, Metro Pictures showed them and Calvin Tomkins noted, in the New Yorker, they were, in fact, ‘’ misunderstood by a number of political-minded art students (male and female), who accused Sherman of undermining the feminist cause by depicting women in ‘vulnerable’ poses’’.

Yet, through these moments, Ms. Sherman remained unwilling to directly tie her work to feminist theory. This tension became especially clear with her Untitled #93, from 1981, a centerfold featuring a tearful girl drawing her bedsheets close.

The girl was interpreted by the many critics as a survivor of sexual assault. But, according to the Sherman’s state, the inspiration was a woman who had gone to bed moments before the sun rose, following a night of debauchery.

This example is typical of the debates that have surrounded Sherman and her work: the artist’s account of her own intentions often conflict with the scholarly debates about feminism and the role of the women in her pictures.

Disasters and Fairy Tales, from 1985 to 1989, much darker endeavour than its prettified predecessor; he gloomy palette and scenes strewn with vomit and mold challenged viewers to find the unqualified grotesque and the beauty in the ugly.

Her photographic portraiture is intensely grounded in the present, but also extends long traditions in art, that force the audience to reconsider cultural assumptions and common stereotypes, among the latter political satire, the graphic novel, caricature, stand-up comedy, the pulp fiction and the other socially critical disciplines.

History Portraits

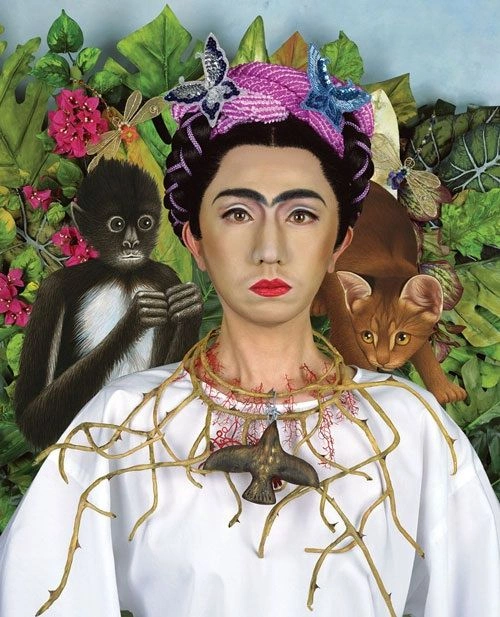

Sherman’s History Portraits, again presented herself as a model, but this time, she assumed the air of European art history’s most famous leading ladies. Leaving in Europe at the time of its creation, she was absorbed in the West’s great museums.

That interlude gave way to Sherman’s Sex Pictures, in 1992, in which she substituted her own figure for that of a doll, and her main intention was to shock and scandalize the public; the images present close-ups of doll-on-doll sex scenes and prosthetic genitalia.

Theatre

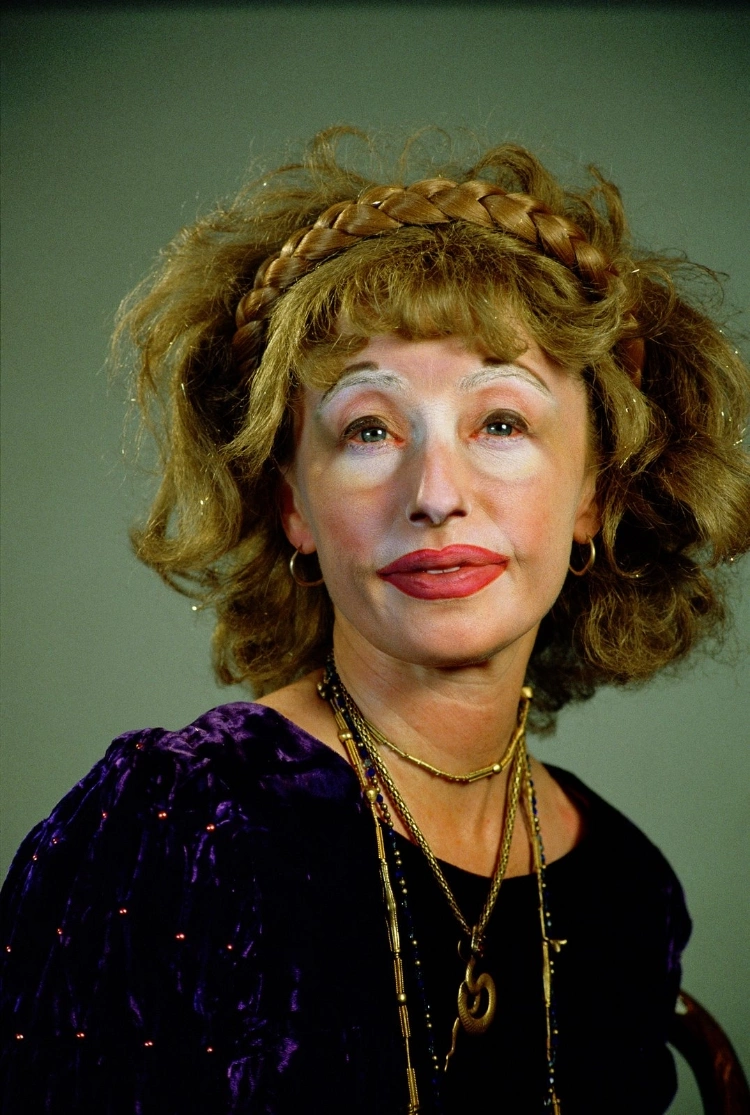

Over the last decade, Sherman dons clown’s make-up in a series of still photography, in 2003, and even more recently, she explored carefully staged female suburban identities in solo show in New York, in 2008.

Also, in her latter series, she photographed herself in various states of awkward make-up, superimposing stodgy, highly-conscious portraits over contrived domestic and faux-monumental backdrops.

Recalling a long tradition of theatrical role-playing in art and self-portraiture, Cindy Sherman uses the camera and the various tools of everyday cinema- costumes, makeup, stage scenery to re-create common illusions, or iconic ‘snapshots’, that signify very different concepts of self confidence, entertainment, public celebrity, and other socially sanctioned, existential conditions.

Although they constituted only a first premise, these images begin to unravel in various ways that suggest how self identity is often an unstable compromise between personal intention and social dictates.

Yet, with each passing year, Ms, Sherman’s art deviates more noticeably from a basic postmodern tenet and the so-called ‘death of the author’, but this idea holds that there is no such thing as originality, that we are all formed by external forces and that identity is completely constructed, which implies that it is also completely de-constructable.

Appropriation

Many variations on the methods of self-portraiture share a single, notable feature: in the majority of Sherman’s portraits, she directly confronts the viewer’s gaze in order to suggest that an underlying penchant for deception is perhaps the only value that truly unites us.

Many critics and art historians have explored the idea of Sherman’s appropriating the ‘’male gaze’’ and the voyeuristic feeling of the works. The artist twists the traditional formula of pin-up shots, and plays into the male conditioning of looking at photographs of exposed women, but she takes on the roles of both, male photograph and female pinup.

Critical

Cindy Sherman epitomizes the 1980s technique of ‘image-scavengering’ and ‘appropriations’ by artists seeking to question the so-called truth-potential of mass-imagery and its seductive hold on our individual and collective psyches. Sherman depersonalized approach to portrait photography has suggested a new, socially critical capacity for a medium that was once presumed a tool of documentary realism or aesthetic pleasure.

This ‘readymade’ quality of the critically applied photograph, whereby a preexisting image or convention is appropriated intact by artist and turned into something more conceptually problematic, if not psychologically disturbing, has come to characterize much work of a new generation defying easy categorization.

About David Fox

David Fox is an artist who created davidcharlesfox.com to talk about art and creativity. He loves to write, paint, and take pictures. David is also a big fan of spending time with his family and friends.

Leave a Reply

|

|

|

|

Now get FREE Gifts. Or latest Free phones here.

Disable Ad block to reveal all the secrets. Once done, hit a button below

|

|

|

|