Lee Krasner – Out of the Shadows

by David Fox

Lee Krasner may not be a name you immediately recognize, but her husband, Jackson Pollock, definitely is a staple in the abstract expressionist community.

Lee Krasner worked tirelessly for over 50 years, continuously pushing the boundaries and her work forward.

She was known for reinventing herself and creating various pieces that range from collage, cubist drawings, assemblage, and abstract expressionism.

While some believe Jackson Pollock overshadowed her, she was one of his biggest fans and one of the most essential crusaders in his legacy.

“I happened to be Mrs. Jackson Pollock, and that’s a mouthful. I was a woman, Jewish, a widow, a damn good painter, thank you, and a little too independent.”

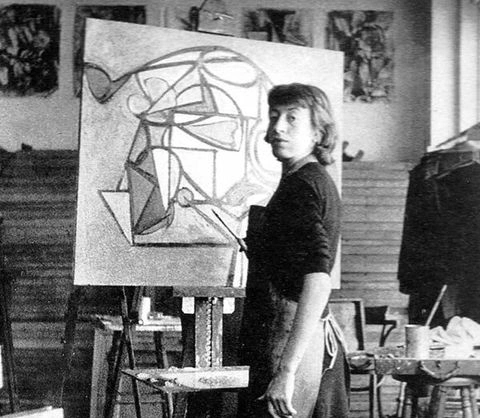

Born in 1908 to Russian-Jewish refugee parents in Brooklyn, Lee knew that art was her passion from her early years. She would attend the Women’s Art School at Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design.

The Museum of Modern Art opened in 1929, and she said, “It was like a bomb that exploded…nothing else ever hit me that hard until I saw Pollock’s work.” She would paint murals for the Works Progress Administration.

She studied with Hans Hofmann in 1937 when she joined the American Abstract Artists Group. She was in the middle of the exciting New York art scene.

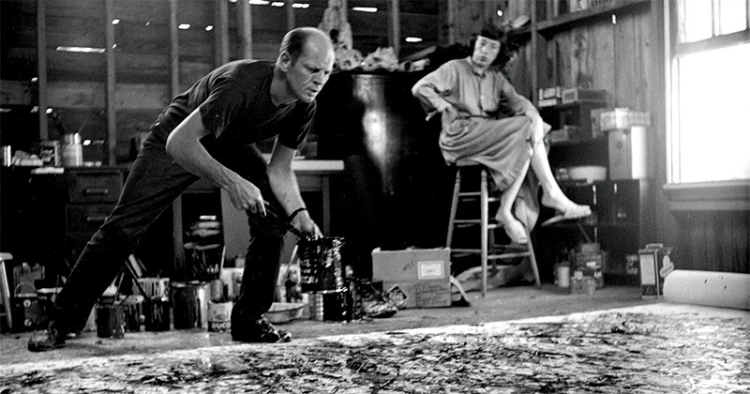

In 1942, Krasner and Pollock were brought together by being included in a significant exhibition, French and American Painting for Graham.

When Krasner decided to knock on Pollock’s apartment door to view his work. This moment was the start of their relationship, which would impact her career.

Krasner introduced Pollock to many influential artists, like Hoffman, Janis, de Kooning, and art critic Clement Greenberg. The two married in 1945 and moved to Long Island.

Krasner spent her days working in her personal studio, creating the Little Images series, which would be her breakthrough work and collages made from discarded Pollock scraps and her admiration for Matisse.

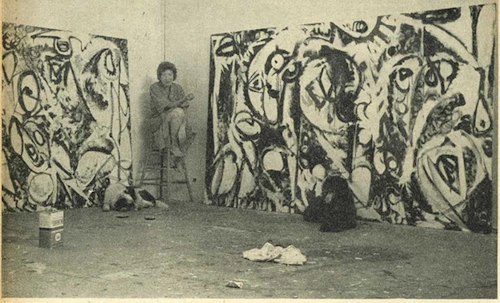

Pollock tragically passed in a car accident in 1956 while Krasner was in Europe. The next year, Krasner moved into Pollock’s barn studio on their property, and she continued working on her craft.

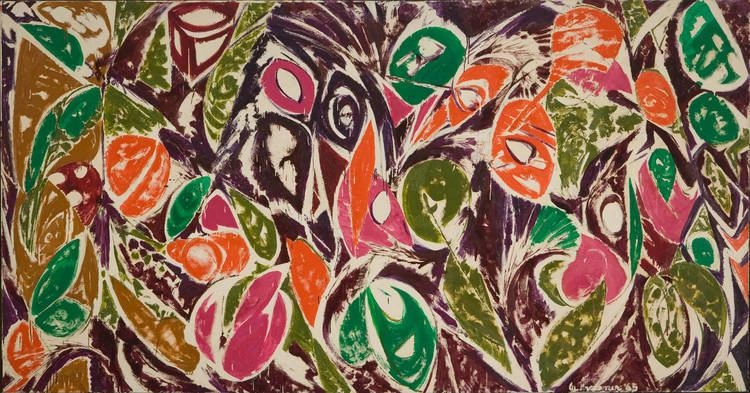

The Seasons (1957) and Gaea (1966) were the beginning of her creations, where nature was an immersive and clear theme.

Her first solo exhibition would come in 1965 at Whitechapel Gallery in London and then in 1975 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. She passed away in 1984, months before her retrospective opened at MoMA.

“I never violate an inner rhythm. I loathe to force anything. I don’t know if the inner rhythm is Eastern or Western. I know it is essential for me. I listen to it, and I stay with it. I have always been this way. I have regard for the inner voice.”

Her Work

Krasner is identified as an Abstract Expressionist because of her expressive works using a variety of mediums.

She has been known to cut apart her pieces, consistently revising and destroying works because she was so critical of herself. Due to this, it resulted in her body of work being small compared to other artists from the same time.

In the 1940s, she was so profoundly impacted by seeing Pollock’s work. She immediately rejected the cubist style she was embarking on under Hofmann.

During this time, the work she produced was referred to as “grey slab paintings,” and she was frustrated with these works. These works were eventually destroyed, and only one work survived this time in her career.

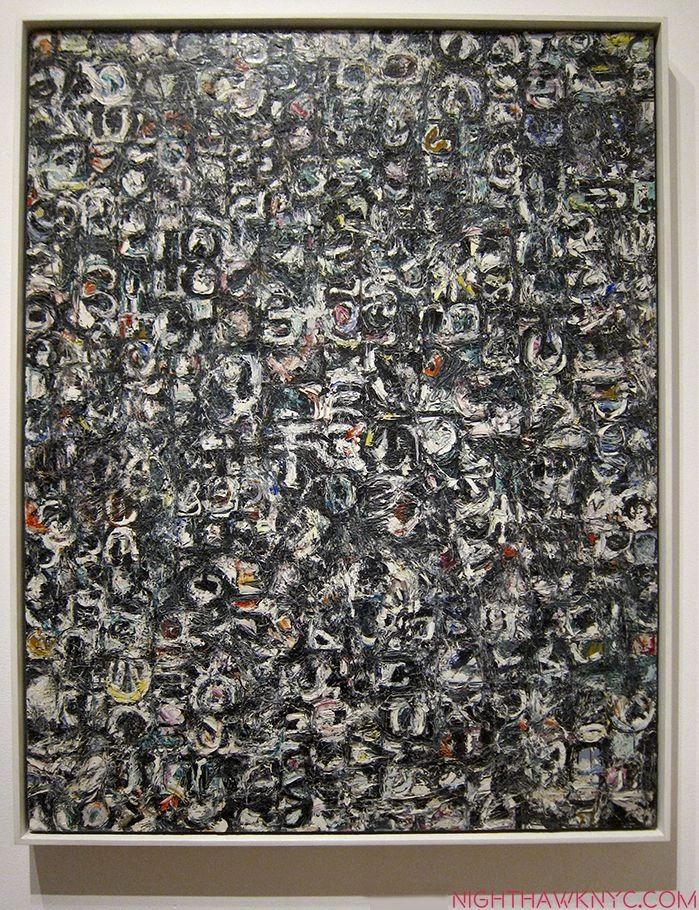

Little Images was her first series, which is 40 small paintings that she created from 1946 to 1949. They’re typically categorized as webbed, hieroglyphs, and mosaic, depending on the image.

The early collage images era was the beginning of her first series of collage paintings. This period was marked by her moving from the easel to the floor.

She would cut and tear shapes onto color field painting used in the 1951 Betty Parsons Exhibition. She would gravitate to a more symbolic manner during this time.

The Earth Green Series was started before Pollock passed away, but she completed the work after his death, reflecting both nature and her feelings of grief. Her intense feelings caused a shift in her art to push more boundaries and her concepts of art.

The Umber Series was developed from 1959 to 1961 when she dealt with insomnia, the grief of her husband’s loss, and the loss of her mother.

She worked during the night, having to use artificial light, so her color story was made up of dull, monochrome colors. She used an aggressive style in this series.

The Primary Series were paintings using bright colors and mimicked a floral or plant-like shape. They were large, didn’t have a focal point and the palettes contrasted one another. Unfortunately, during this time, she suffered an aneurysm, fell, and broke her dominant wrist, so she began using her left hand.

She continued to work on large horizontal paintings with rigid edges with bright colors and a second collage series made up of old charcoal drawings she had done.

Her Legacy

After Pollock died, Krasner began to achieve recognition, like her first retrospective. In the 70s, she became part of the strong feminist movement that was occurring. The movement was quick to champion her story of living in her husband’s shadow.

The 1984 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art that took place months after her death was a big moment for her career. The New York Times said the retrospective “clearly defines Krasner’s place in the New York School.”

They also said that she “is a major, independent artist of the pioneer Abstract Expressionist generation, whose stirring work ranks high among that produced here in the last half-century.”

The Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center at Stony Brook University is one way their legacy lives on.

Until 2008, Krasner was one of four women who had a retrospective show at the institution, the others being Louise Bourgeois in 1982, Helen Frankenthaler in 1989, and Elizabeth Murray in 2004.

Her papers were donated in 1985 to the Archives of American Art and have since been digitized and are located on the web.

The Pollock-Krasner Foundation was established in 1985, and it functions as the estate for both artists, but it also assists working artists of merit with financial assistance.

In 2003, her work Celebration sold to the Cleveland Museum of Art for almost $2 million. In 2008, Polar Stampede sold for $3.2 million.

“All my work keeps going like a pendulum; it seems to swing back to something I was involved with earlier, or it moves between horizontality and verticality, circularity, or a composite of them. For me, I suppose that change is the only constant.”

Sources:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/19/arts/lee-krasner-barbican-schirn-kunsthalle.html

https://www.moma.org/artists/3240

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/lee-krasner-more-than-a-muse-1854144

https://www.azquotes.com/author/8259-Lee_Krasner

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lee_Krasner

https://www.thoughtco.com/lee-krasner-biography-4178004

Videos To Watch

About David Fox

David Fox is an artist who created davidcharlesfox.com to talk about art and creativity. He loves to write, paint, and take pictures. David is also a big fan of spending time with his family and friends.

Leave a Reply

|

|

|

|

Now get FREE Gifts. Or latest Free phones here.

Disable Ad block to reveal all the secrets. Once done, hit a button below

|

|

|

|