Mary Cassatt – Famous Women Artists In History

by David Fox

I think that if you shake the tree, you ought to be around when the fruit falls to pick it up.

One of the leading artists in the Impressionist movement, Mary Stevenson Cassatt was born on May 22, 1844, in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania. She was born and growing up in a comfortably upper-middle-class family: her mother belonged to a prosperous banking family, and her father was well-to-do real estate and stockbroker.

Her elementary schooling prepared her to be a proper wife and mother, included such classes like embroidery, music, homemaking, painting and sketching.

Not For Girls

Her upbringing reflected her family’s high social standing; Cassatts lived in Germany and France, from 1851 to 1855, giving the young girl an early exposure to European culture and art history. As a child she had learned French and German, and these language skills served her well in her later career.

She may also have visited the Paris World’s Fair at 1855, at which she would have viewed the art of Eugène Delacroix, Gustave Courbet, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Auguste-Dominic Ingres among other French artists.

At the age of 16, Mary started studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Not surprisingly, she found the male faculty and her fellow students to be patronizing and resentful of her attendance.

She also became frustrated by the inadequate course offerings and curriculum’s slow pace. However, she decided to leave the program and move to Europe, where she could study the works of the Old Masters, firsthand, on her own.

Despite her family strong objections and their initial misgivings; her father declared that he would rather see his daughter dead than living abroad as a ‘bohemian’, Mary Cassatt left for Paris, in 1866.

In Paris, she studied with Jean-Leon Gérôme and had the private art lessons in the Louvre, where she copied the great masterpieces of art. This, of course, greatly influenced her own skills as a painter.

Discovery

Mary continued to paint and study in relative obscurity until 1868, when one of her portraits was selected for the annual exhibition at the prestigious Paris Salon. The well-received piece of her was submitted under the name Mary Stevenson.

In 1870, after the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, Mary Cassatt returned home to live with her family. Upon her return to the outskirts of Philadelphia, the artistic freedom she enjoyed in Paris, immediately extinguished; she was pretty much frustrated by a lack of artistic resources and opportunities.

Not only did she have trouble finding proper supplies, but her father refused to pay for anything connected with her art. In order to raise funds, she tried to sell some of her paintings in New York, but to no avail.

She tried to sell them once again, through a dealer in Chicago, but her paintings were tragically destroyed in a fire, in 1871.

In the midst of these difficult circumstances, Mary was contacted by the archbishop of Pittsburgh, who wanted to commission her to paint copies of two works by Correggio, an Italian master. She accepted the assignment and left immediately for Europe, where the originals were, in Parma, Italy.

With the money she earned from the commission, she was able to sit out again for Paris and resume her career in Europe. In this period, the early 1870s, she also traveled to Spain and Holland, where she familiarized herself with the work of the most famous masters, such as Diego Velásquez, Peter Paul Rubens, and Rembrandt van Rijn.

The Paris Salon accepted her paintings for exhibitions in 1872, 1873 and 1874, which helped secure her status as an established artist; she continued to paint and study in Rome, Belgium, and Spain and eventually settling permanently in Paris.

Paris

By 1874, she had established herself in a studio in Paris. Three years later, her parents and her sister Lydia joined her in France. They frequently served as models for her work of the late 1870s and 1880s, which included many images of contemporary women at the opera and theatre, in parlors and gardens.

Self-reliant and single-minded, Mary had the opportunity to concentrate on her art in a city where, ‘’women did not have to fight for recognition if they did serious work’’.

Though she felt indebted to the Salon for building her career, Mary Cassatt began to feel increasingly constrained by the inflexible guidelines and traditional tastes of Paris’s official art scene. She began to experiment artistically, no longer concerned with what was commercial or fashionable.

During this time, she drew courage from painter Edgar Degas, whose pastels inspired her to press on in her own direction; her new work drew criticism for its bright colors and unflattering accuracy of its subjects.

When Edgar Degas invited her to join the group of independent artist, known as Impressionists, in 1879, she was delighted. The impressionists’ show was a huge success, commercially and critically, and her admiration for Degas and Impressionists would soon blossom into a strong friendship.

Cassatt exhibited her work with the Impressionists in Paris from 1879 onwards; in 1886 she was included in the first major exhibition of Impressionist art in the United States at the Durand-Ruel Galleries in New York.

Honest Portraiture

While many of her fellow Impressionists were focused on landscapes and street scenes, Mary became famous for her portraits. She continued to specialize in scenes of women in domestic interiors, especially mothers and their children, with an Impressionist emphasis on quickly captured moments of contemporary life.

Also, she shared with the Impressionists a general conviction that academic art was outdated and a commitment to explore fresh new means of everyday modern life.

Cassatt’s portraits were unconventional in their direct and honest nature, and her constant objective was to achieve force, not sweetness, truth, but not sentimentality and romance. These works, like all her portrayals of women, may have achieved such a popular success for a specific reason: they filled a societal need to idealize women’s domestic roles at a time when many women were, in fact, beginning to take an interest in voting rights, higher education, dress reform and social equality.

Yet, Cassatt’s depictions of her fellow upper-middle-class and upper-class women were never simplistic; they contained layers of meaning behind the airy brushwork and fresh colors of her impressionistic technique.

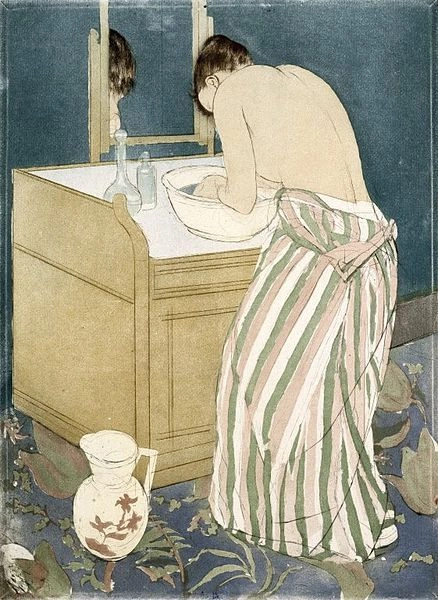

In her piece The Child’s Bath, from 1893, an intimately observed vignette of a woman bathing her child, Mary combines certain stylistic influences of Japanese art with the subject matter of her own milieu.

The variety of patterns in this composition, including several floral designs and the bold stripes of the woman’s dress is united by a restrained palette of greys and mauves. The soft coloration allows the viewer to concentrate on the subject of the scene- the close relationship between mother and child.

Their intimacy is demonstrated by their closely positioned faces and by the circle of touch that extends from the woman’s hand on the child’s foot to the child’s hand to the woman’s knee. In this work, Cassatt evoked the traditional artistic subject matter of the Madonna and Child, making her imagery rather secular then religious.

Regarding her artistic style, she expanded her technique from oil painting and drawing to pastels and printmaking. Japanese wooden prints had been very popular in Paris since it was featured at the 1878 Exposition Universelle, and Cassatt, like many other Impressionist, incorporated its visual devices into her own work.

Experimentation

Mary Cassatt’s painting style continued to evolve away from Impressionism in favor of a simpler, more straightforward approach. Her final exhibition with the Impressionists was in 1886, and she subsequently stopped identifying herself with a particular movement or school.

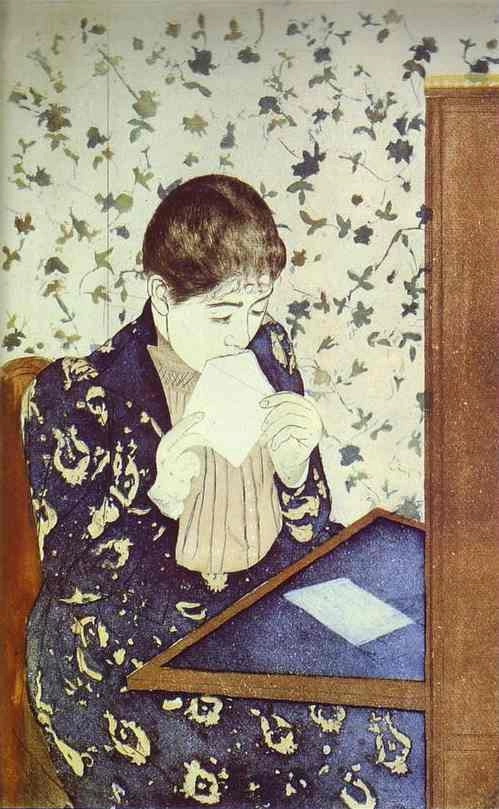

Her experimentation with a variety of techniques often led her to unexpected places. For instance, her Letter, from 1890/91, shows a woman sealing a letter she has just written at her desk.

The composition balances patterns- the wallpaper and the woman dress, against solid areas of color, the vertical back of the desk, the paper of the letter and envelope; brings the viewer close to the room’s shallow space, where forced perspective is evident in the oddly skewed writing panel of the desk.

These stylistic choices were influenced by traditional Japanese printmaking- the direct reference to Bijinga Ukiyo-e , the wooden prints of Kitagawa Utamara; yet, the woman’s garments and the other objects are all contemporary details of Cassatt’s world.

After 1890, Mary suffered from failing health and deteriorating eyesight, but she maintained close relationship with her artist friends and important art world figures in France and America. Although she and Degas suffered a rift in their friendship during the infamous Dreyfus affair, of the late 1890s, they later made amends.

In 1904, Cassatt was recognized for her cultural contributions by the French government, which awarded her the order of Chevalier of the Legion d’honneur.

Egypt

A 1910 trip to Egypt with her brother, Gardner, and his family, would prove to be a turning point in Mary Cassatt’s life. The Egyptian magnificent ancient art made her question her own talent as an artist.

Soon after their return home, Gardner died unexpectedly from an illness he contracted during the journey. These two events deeply affected Cassatt’s physical and emotional health and she was unable to paint again until around 1912.

Three years later, she was forced to give up painting altogether as diabetes slowly stole her vision. For the next 11 years, until her death- on June, 14, 1926, in her country home a chateau located in Le Mesnil- Théribus, fifty miles northwest of Paris- Marry Cassat lived in almost total blindness, bitterly unhappy to be robbed of her greatest source of pleasure.

Mary Cassatt had never married nor had children, choosing instead to dedicate her entire life to her artistic profession. By her late years, she was able to witness the emergence of modernism in Europe and the United States, but her signature style remained consistent.

The waning critical taste for Impressionism after her death meant that her influence on other artists was limited.

Legacy

She is considered one of the most important American expatriate artists of the late 1800s, along with James Mc Neill Whistler and John Singer Sargent. She has also been the focus of influential scholarship on female artists and her work has been discussed by key feminist art historians including Linda Nochlin and Griselda Pollock.

However, Cassatt’s status in art history has been significant and influential in the later twentieth and twenty-first centuries. She became a key figure in the fin de siècle art world and helped to establish the taste for impressionist art in her native United States.

About David Fox

David Fox is an artist who created davidcharlesfox.com to talk about art and creativity. He loves to write, paint, and take pictures. David is also a big fan of spending time with his family and friends.

Leave a Reply

|

|

|

|

Now get FREE Gifts. Or latest Free phones here.

Disable Ad block to reveal all the secrets. Once done, hit a button below

|

|

|

|