Still Lifes of Suzanne Valadon – Where No “Decent” Woman Would Tread

by David Fox

Much has been said on the nudes of Suzanne Valadon, and rightly so.Truly, they are wonderfully composed and naturally iconoclastic in nature.

Women.Real women portrayed in natural scenarios by other women was unheard of in the late 1800s and into the 1900s.Generally women did not tackle nudes at all; the powers that be fearing the practice would corrupt delicate souls.

Valadon, exempt from propriety due in part to humble birth and in other part her choice of tawdry career as an art model, was able to express herself in ways other women could or would not at the time.

She was admitted into salons (where no “decent” woman would tread) and even found herself the first woman painter of Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (SNBA), in 1894.

Here she is pictured with her son, Maurice, in 1889.

All this is quite spectacular on its own, but I would like to leave the icon smashing and feminist critique behind for a short while. I’d even like to leave the entirety of her personal life behind. Today we will look at Valadon as a genderless painter of fruit and flowers. We will examine her still lifes and perhaps see the merit the SNBA saw when they chose to add her to the pantheon of art gods.

Bouquet de Roses dans un Obus, oil on card, 1913

One of my favourites, Suzanne places roses inside an obus (cannon shell).To the roses she gives definition with her characteristic heavy lines.To the obus, however, she uses soft short strokes.

This renders an object of war nothing more than a harmless vase.The placement of the object on a kitchen sill next to feminine lilac drapes annihilates the last bit of danger to the point that the obus loses its meaning entirely.

Even knowing what cannon shells of the period look like, a viewer would be hard pressed to identify it as such.Bordering on symbolist, she keeps the colours orthodox and avoids contrivance.

It is a balanced work that evokes a timely “Frenchness”, and a little titter at the tender emasculation of a phallic object (whoops, some feminist critique slipped in).

Untitled, oil on card, 1930

Speaking of timely Frenchness, what could be more delightfully 1930s French than a blue vase stuffed with roses?Never a servant of style, Valadon takes a more post impressionist (but not quite) look at these flowers.

Her beautiful built up highlights and shadows are made somehow more realistic by the presence of clear brushwork.The flowers are lit up from within.

Her choice of perspective is ever so slightly naïve, causing the vase to float, lending extra emphasis to it as a focal point. Objects in the background are arranged firmly in reality though, grounding the whole thing on what I’m sure was a wonderfully printed tablecloth.

Valadon painted many roses, tulips, orchids and the like, but her greatest still lifes often involved the honesty of circumstance her nudes had in spades as well.

A common basket of even commoner duck eggs waits quietly for the cook, nestled in straw.The stonework is alive with colour, both in light and shadow.

Valadon does not half paint even the most simple of highlights. The way the light falls over the eggs and onto the wall brings to mind an open door; perhaps the cook has come for these blue cast beauties at last.

Basket of Duck Eggs, oil on card, 1931

Nature Morte au Lièvre, Faisan et Pomme, oil on card, 1930

Pieces like, Still life with Hare, Pheasant and Apple, convince us of Suzanne’s sense of humour.An old hare dangles almost peacefully from hind legs drained and awaiting a competent cook to relieve it of its skin in one swift pull.

The young pheasant seems to be dreaming grand, worried dreams despite its questionable life status.Apples sit pertly on a plate, as if to rub in how alive they are; not knowing they all share the same fate.

A quick laugh is had at the idea of a “nature morte” of dead animals.It’s so on the nose if it weren’t for the sombre, reverent overtones this piece would risk vulgarity.As it stands though, in characteristic Valadon style, she goes just far enough.

We feel the ambivalence of the old hare, the tragedy of the young pheasant and the haughtiness of the apples.It mirrors truth, not to mention the sanctifying warmth pervading the scene is downright Fauvist.

Given her close ties with Ganguin, this is unsurprising. Suzanne’s emotional colour vocabulary is extremely developed across her still lifes and painted portraits.

So far the emphasis has been on her later, more developed works, but what of earlier material?

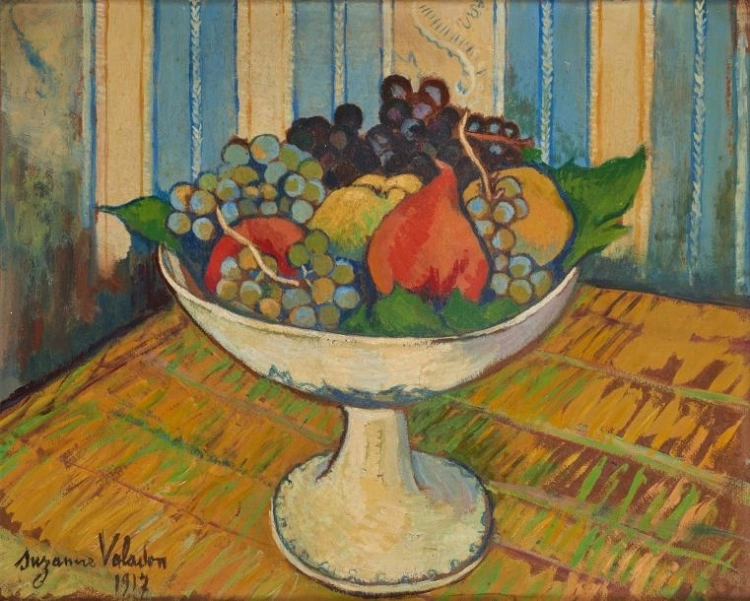

Nature morte au compotier de fruits, oil on card, 1917

Again, nearly symbolist in nature, this fruit bowl is absolutely uncommon.Her slight naivete of perspective keeps a sense of stuffy refinement far away from her popular and often grossly academic subject.

Colours, simply layered, build a juicy pear and living grapes. She bothers to paint the calyx of an upside down apple though. In fact, this composition is rife with luxurious, unnecessary details.

The brocade stripes of the wall cover, blue details on the china pedestal bowl and the delicately defined wicker table stand in sharp contrast to the relatively faceless fruit.

She forces the viewer to realize detail in objects she omitted it from. Like so many excellent paintings, it is what is left unpainted that is remarkable.

Remarkable works, Valadon has many.In her time she was a immensely popular and respected artist, though time can cruelly erase that which does not fit the appropriate narrative.

Suzanne, when she is mentioned at all, is mostly talked about in terms of being a revolutionary woman (she was) or being a woman in the den of great men (Ganguin, Cezanne, Latrec…).

Her life is often cast, if cast at all, in the red glow of bawdiness thanks to the childish puritanism of our modern world.This I think, though titillating, is unfair.

Her work shows a greatness of spirit and a delicacy of soul.She mastered the concepts of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’; played with humour and nuance.

Everything about her art suggests an actualized, inspired, aspiring mind.If anything, Valadon achieved in life what most artists only achieve in death.

The respect and admiration of her peers. It would be wonderful if she were appreciated in death the way she was lauded in life.

Let us quietly appreciate a grouping of more typical Valadon still lifes and see what Gauguin saw in a talented, young art model so many years ago.

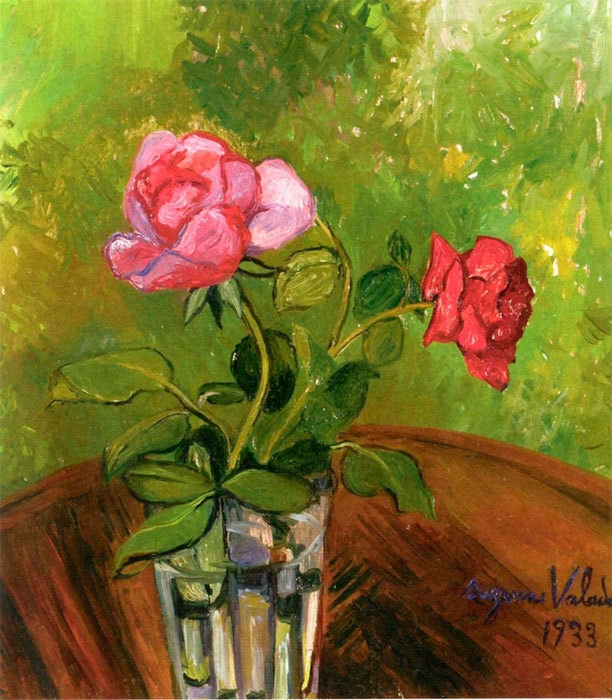

Bouquet des Fleurs 1937

White Fruit Bowl undated

Roses dans une Verre 1937

Her confident lines are instantly recognizable as is her slightly off perspective.Even working with universal subjects, she manages to make every vignette intensely personal.

Her still lifes are as intimate, in my opinion, as her nudes and deserve as much notoriety in popular art critique beyond the French Riviera. Though, it must be said again, her nudes are extremely worthy of examination.

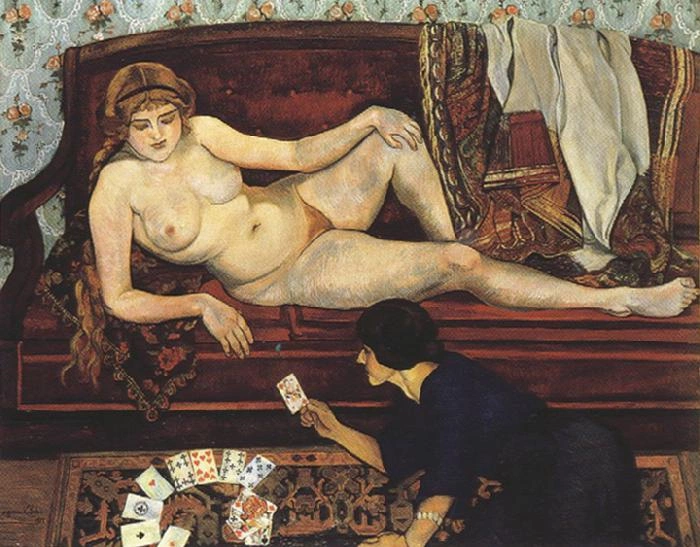

The Future Unveiled, 1912

So please, no more of this “Mistress and Muse of Montmartre” crap that appears in so much analysis of her.When it comes to Valadon there is plenty to talk about inside the frame.

Speculating on the woman more than the work does no one any favours and has constantly robbed the present of the honest presence of a brilliant artist.Suzanne Valadon; a Crown Jewel of Montmartre.

This is her rightful place and there she will live in my heart and mind forever.

Photo of Valadon, Photographer and date unknown

About David Fox

David Fox is an artist who created davidcharlesfox.com to talk about art and creativity. He loves to write, paint, and take pictures. David is also a big fan of spending time with his family and friends.

Leave a Reply

|

|

|

|

Now get FREE Gifts. Or latest Free phones here.

Disable Ad block to reveal all the secrets. Once done, hit a button below

|

|

|

|