The Superflat Art Movement And Its Purposeful Absence Of Depth

by David Fox

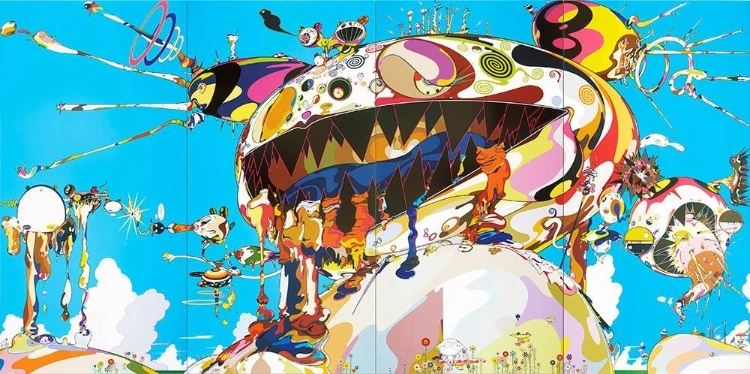

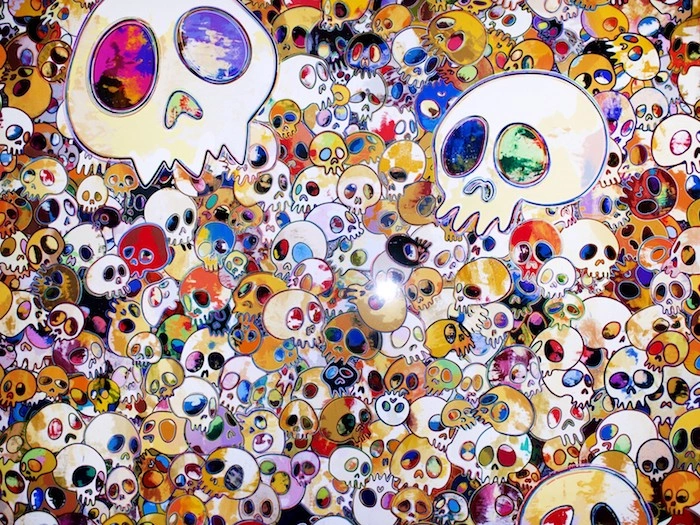

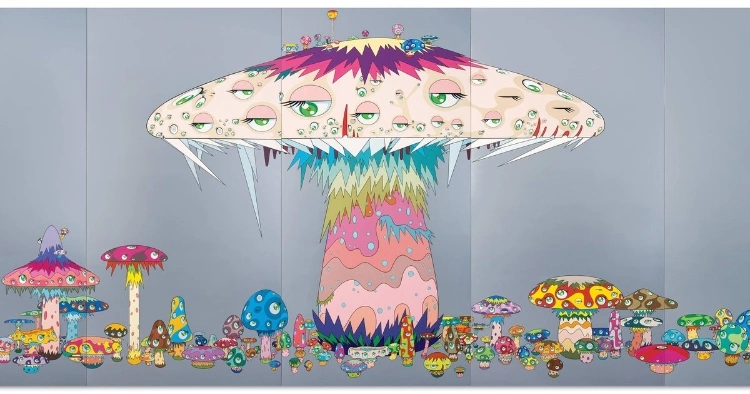

It can be seen that embedded in the apparently vivid Superflat works, with their total absence of depth, are a variety of cultural, political, social, and historical contexts concerning the relationships between high art and subculture, between Japan and America, between contemporary art and capitalism. If we place these contexts within brackets and pretend to ignore them, the strength of the high quality, super flat surface is most apparent, but the moment we summon up these contexts, the picture starts to hint at endless meanings. Smoothness and complication, beauty and high-functionality, Murakami imbues his paintings with unparalleled structure, a structure that resembles an incredibly carefully planned, highly-functional cyborg.

Minami, 2001.

Superflat

Superflat was launched in Tokyo, 2000, through the Superflat exhibition which was designed to travel globally. An elaborate, bilingual catalogue Super Flat was produced to accompany the exhibition which included Murakami’s “A Theory of Super Flat Japanese Art”.

It was the first in a trilogy of exhibitions curated by Murakami. According to the artist, the trilogy of Superflat exhibitions were constructed to provide a cultural and historical context for the new form of Superflat art that he was proposing, and which was specifically exported for Western audiences.

The theory of Super Flat art is a manifesto for Murakami’s concept of a new form of art emerging from the creative expressions produced in Manga (graphic novels), video games, anime (Japanese animation), fashion and graphic design.

In this theory Murakami identifies Superflat as a genealogy of aesthetics tendency in which contemporary Japanese culture has inherited a spirit of artistic innovation and creativity from the Edo period, 1600-1867.

The concept of a Superflat aesthetics lineage draws significantly on Japanese art historian Tsuji Nobuo’s Kisō no Keifu (Lineage of Eccentrics, 1970).

Nobuo identified a common disposition among six Edo artists to ‘the production of eccentric and fantastic images’, and also identified a tendency toward playfulness and eccentricity in contemporary forms of manga and anime.

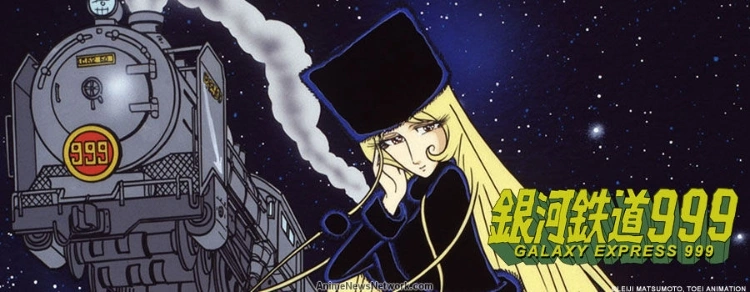

Murakami extends Nobuo’s argument by presenting Superflat as an aesthetics that reinforces the two-dimensionality on the surface, a feature which he also recognizes in the paintings of the Edo Eccentrics (these include Iwasa Matabei, Kanō Sansetsu, Itō Jakuchū, Soga Shohaku, Nagasawa Rosetsu and Utagawa Kuniyoshi) and anime texts such as Galaxy Express 999.

The Superflat planar emphasis is achieved through a composition structure that directs the viewer’s gaze across the surface of the painting, rather than drawing it in through the conventions of Western linear perspective.

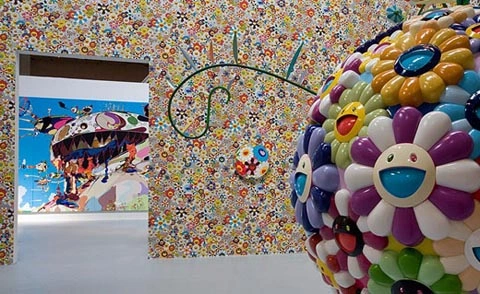

In addition, Superflat can also be used to describe the visual style of Murakami’s works. In his own sculptures, paintings and other assorted productions Murakami appropriated the kawaii character icons and two-dimensional aesthetics of manga and anime and combines these with compositions and techniques derived from the traditions of Japanese painting.

Modern Art? No, Modern Edo.

By connecting Edo forms of Japanese painting with the contemporary commercial expressions emerging in manga, anime, fashion, video-games and graphic design, Murakami presents Superflat as a merging of art and popular culture and a questioning of the culturally and socially constructed definition of art, especially in Japan.

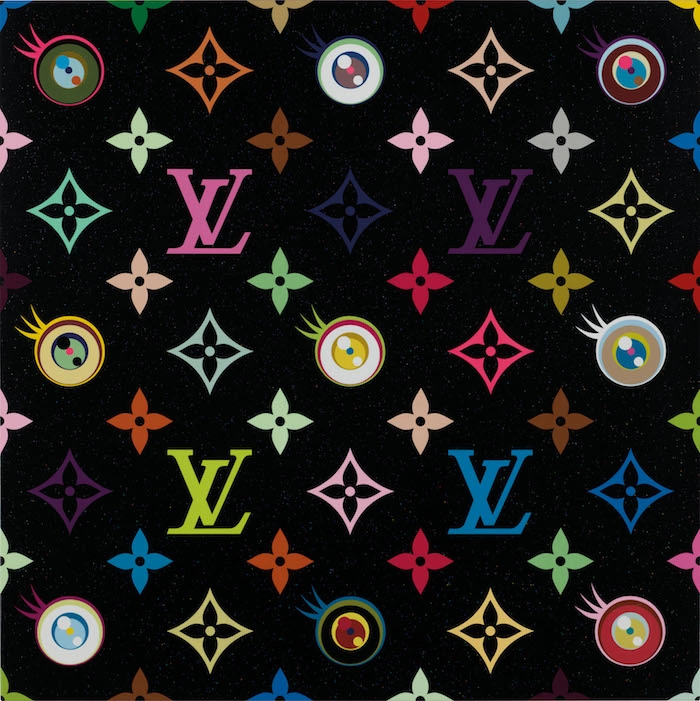

In his own work, the artist reinforces this merging of art and commercial culture by producing sculptures, paintings, handbags, snack toys, key-chains, t-shirts, buttons, stickers and bandanas which are all based on the same Superflat iconography.

Murakami presents the production of his art as a business strategy and challenges the conventional avenues for the exhibition of art Japan.

Therefore, Superflat theory is also driven by a more politicized commentary on the modern institutions of bijutsu (fine art) in Japan.

Murakami rejects the modern institutions of kindai bijutsu (modern art) which he considers to be an incomplete importation of Western concepts and institutions of art since their adoption in the Meji period (1868-1912) as part of the process of modernization and westernization.

To Murakami, the innovation and originality of contemporary forms of commercial culture represents a continuation of the innovations introduced by the premodern eccentric artists.

Murakami argues that these qualities of creative invention and avant-garde spirit were excluded from the practices and institutions of bijutsu, and that it is the texts and practices of contemporary consumer culture that offer the re-emergence of what he considers to be authentic and original Japanese expression.

POKU

The concept of revolutionizing art was drawn from Murakami’s early aim to merge Pop Art with otaku production-consumption practices in order to create a new form of popular art, POKU.

Otaku refers to groups of manga and anime fun communities who are conventionally described as ‘hard-core’ and are prevalent throughout Japan.

While the aim of POKU was to market art in otaku cultural institutions, Murakami declared this project a failure and decided to focus on transforming the consumption of art in Japan and to bring a new form of art in Japan, although one that was still influenced by otaku culture, to Western art world.

Thus POKU was superseded by Superflat’s intention to harness the creative expressions being generated in the production-consumption of commercial culture more generally.

A critical component of this strategy is Murakami’s art studio/factory Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd., formerly known as Hiropon Factory; the studio produces Murakami’s works and associated products which are sold through the studio website and stores, but also provides exhibition opportunities for emerging artists.

Western Invasion or Eastern Affirmation?

However, Murakami’s concept of Superflat art, and the artworks that represent it, attracted significant media and gallery attention leading to an important turning point in Murakami’s profile in Western contemporary art worlds.

The subsidiary politic in Superflat is the affirmation of its Japanese identity in an almost recalcitrant swipe at Western art. Murakami presents it as a type of post-Pop, an indigenous expression of Pop Art.

At the same time, Murakami acknowledges the transformations of Superflat expression under the influences of Western culture.

This position is even more complex because Murakami also explicitly emphasizes his strategy to successfully sell work in the United States and European art markets- around 70% of his paintings and sculptures are sold in these markets.

Therefore while a key aspect of his project is to affirm the Japanese identity of Superflat art, it is also self-consciously presented in the codes of Western art worlds and art markets.

At the same time, Murakami is using Western art markets, and the popular appeal of Japanese consumer culture both in and outside Japan, in order to propose alternatives to the institutions and practices of bijutsu in Japan.

It is this tension and dialogue between the commodification of Superflat and the simultaneous challenge to existing forms of art production-consumption, through the merging of art and commercial culture, which makes the analysis of Superflat complex.

This complexity arises because the meanings of commodity, art and cultural identity are themselves contested concepts in contemporary culture, especially in the context of globalization.

Contemporary culture can be defined by the multidimensional relations that constitute the economic, cultural and political processes of contemporary globalizations.

Art, as a central mode of human ‘expressivity’, defines and shapes culture. As the interaction between social groups has become increasingly globalized, the meaning-making and expressivities associated with art have also become engaged through national and transnational gradients.

Murakami’s work and Superflat theory are significant as they expose the key debates in contemporary culture regarding the relationship between art and commodity which are part of broader debates on the meaning of art in relation to consumer capitalism and the production of art in the processes of contemporary globalization.

The formation of identity and expressive modes within a national genealogy becomes particularly problematic within a globalizing cultural sphere.

The articulation of a particular kind of ‘national identity’ in Murakami’s work problematizes the global-local compound and a cognition which celebrates hybridity and postmodern open identities.

The analysis of the concept and expression of Superflat demonstrates the potential for diverse interpretations which challenge and move away from Murakami’s own presentation and understanding.

Particularly, Murakami’s works and Superflat can be understood as expressions of the complex relations between cultural identity, art and commodity in the contemporary cultural context in which they are produced-consumed.

Trading Faces

The Japanese identity of Superflat is pretty complicated. Superflat echoes conventional constructions of a Japan/West binary which obscures the connections and power relation in this structure.

Secondly, while Murakami acknowledges the Western influences on the Superflat aesthetics, his simultaneous transposing of this hybrid identity into a reinforcement of a Japanese identity, characterized by cultural assimilation and hybridization, reinforces a unified national-cultural identity.

This identity is supported by the references between Superflat and already existing discursive constructions of Japanese culture and as flat.

Also, Superflat is part of ongoing trade relations and cross-fertilizations of visual culture forms between Japan and the West since the late nineteenth century.

These complex relationships demonstrate the need to locate Superflat in a global context and to critically interrogate Murakami’s concept and aesthetics.

Murakami’s work and Superflat art can be understood to articulate a postmodern aesthetics and conceptualization of art; the flattening of the distinction between commercial commodities and art and expressing the hybridizing effects of global cultural interactions.

The Superflat is terrain of contestation, making both the absence of hierarchical divisions between art and commercial culture and the presence of multiple structures demarcating the various social, political, cultural and historical contexts in which Superflat engages as it circulates globally.

This fluidity is often negated by the responses to Murakami’s work illustrated in the introductory quotes, which continue to affirm an art/commodity distinction: Murakami’s work is either defended as an aesthetic critique of the socio-cultural condition of commercial consumption or decried as a celebration of the lack of distinction between commercial production and art.

This simple dualism limits the understanding of Superflat and reveals the persistence, through debates, of the concepts autonomy, authenticity and aesthetic value in relation to definition of cultural identity and art.

About David Fox

David Fox is an artist who created davidcharlesfox.com to talk about art and creativity. He loves to write, paint, and take pictures. David is also a big fan of spending time with his family and friends.

Leave a Reply

|

|

|

|

Now get FREE Gifts. Or latest Free phones here.

Disable Ad block to reveal all the secrets. Once done, hit a button below

|

|

|

|