Yayoi Kusama – Polka Dot Madness

by David Fox

Yayoi Kusama’s work has transcended two of the most important art movements of the second half of the 20th century: minimalism and pop art. Plagued by mental illness as a child, and thoroughly abused by a callous mother, the young artist persevered by using her hallucinations and personal obsessions as fodder for prolific artistic output in various disciplines.

This has informed a lifelong commitment to creativity at all costs, despite the artist’s birth into a traditional female-effacing Japanese culture, and her career’s coming of age in the male dominated New York art scene.

Her extraordinary career spans paintings, performances, room-size presentations, literary works, outdoor installations, sculpture, fashion, films, design, and intervention within existing architectural structures, which allude at once to a microscopic and macroscopic universe.

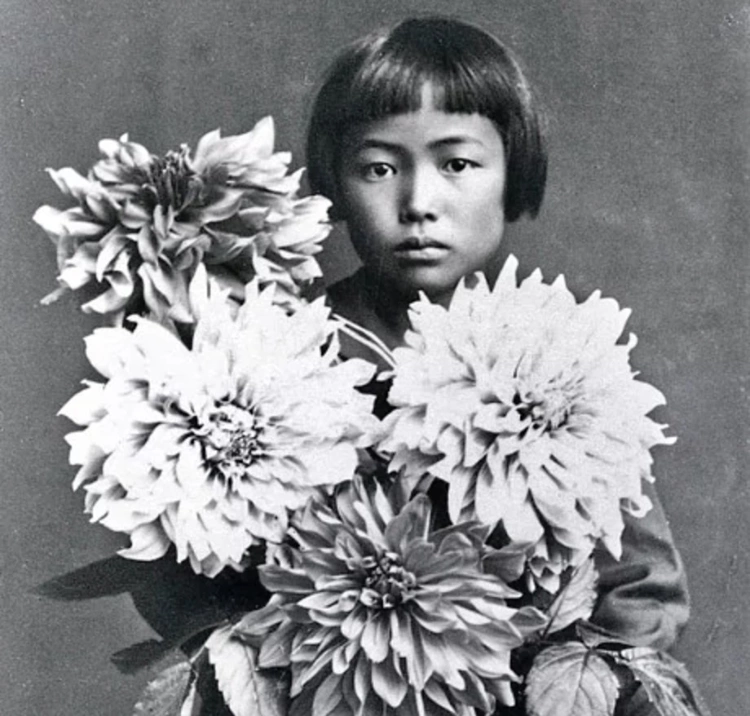

Early Life

Yayoi Kusama was born on March, 22, 1929 in Matsumoto, Japan, as the youngest of four children in a wealthy family. However, her childhood was less than idyllic or perfect. Her parents were the product of a loveless, arranged marriage.

Her father, emasculated by the fact that he had to take his wife’s surname as a condition of marrying into the wealthy family, spent most of his time away from home, womanizing, leaving his angry wife to physically abuse and emotionally torment her youngest child.

She would often send her daughter to spy on her father’s sexual exploits.

When Kusama began to see vivid hallucinations at the age of 10, her way of coping with the bizarre phenomena was to paint what she saw. She says that art became her way to express her mental disease.

For Kusama, art-making became a fundamental survival mechanism; it was her sole tool for making sense of a world in which she dwelt on the periphery of normative experience, and as a result, became the very thing that allowed her to assimilate successfully into society.

Disobeying her mother (who wanted her to simply be an obedient housewife) Kusama studied art in Masumoto and Kyoto. She had little formal training, studying art only briefly, 1948-49, at the Kyoto City Specialist School of Art.

At that time, there was a movement to reject the influences of Western culture in Japan, so Kusama was forced to only study Nihonga, which consisted of creating paintings using 1000-year-old traditional Japanese techniques and materials.

Move To United States

The conservative Japanese culture, and her abusive mother proved too much for Kusama, and 1957, she moved to the United States, settling in New York in the following year. Before she left, Kusama’s mother handed her some money and told her to never set foot in her house again.

In response, Kusama destroyed hundreds of her works.

In the United States, Kusama was free to explore her artistic expressions that were censored while living in Japan. With the help of artist Georgia O’ Keeffe, who Kusama had started a friendship with while still in Japan, she was able to secure exhibitions and also some sales, leading to interest in her work right from the start.

Also, there was a fascination with the foreign artist herself, and she struck up a deep relationship with her fellow artist Donald Judd and the middle-aged assemblage artist Joseph Cornell, who was also infatuated with Kusama, often writing her love letters and sketching her in the nude.

Because of her anxiety and fear of sex, both relationships, while very close, were strictly platonic. Kusama and Cornell developed such a close bond (allegedly, he shared her sexual aversion and hated sex) that when he died in 1972, she began creating collages to honor his work and cope with his passing.

In this period, Kusama worked feverishly, embracing the hedonist, free-spirit hippie culture of the 1960’s, which also included patriarchy, protesting war and capitalist society. Combining these themes with her personal anxieties, she created deeply intimate art, but also spoke to the injustices of the times.

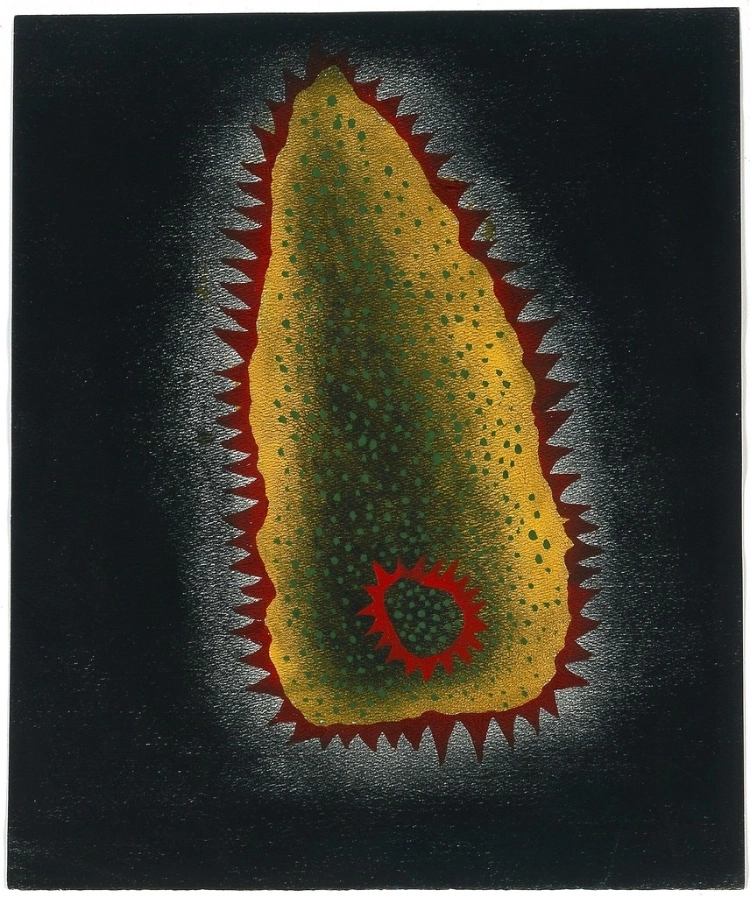

Watercolors

The first works she exhibited in New York were her watercolors. These first works on paper showed the artist breaking free from traditional Japanese artistic practices and she was thought as a child and embracing Western artistic influences, especially in regards to abstraction.

The piece named The Woman, from 1953, is one of these earlier abstract works. The watercolor depicts a singular biomorphic form with subtle dots in the center floating in a seemingly black abyss. The form is reminiscent of female genitalia with red spikes surrounding it.

The overall effect: bizarre and aggressive.

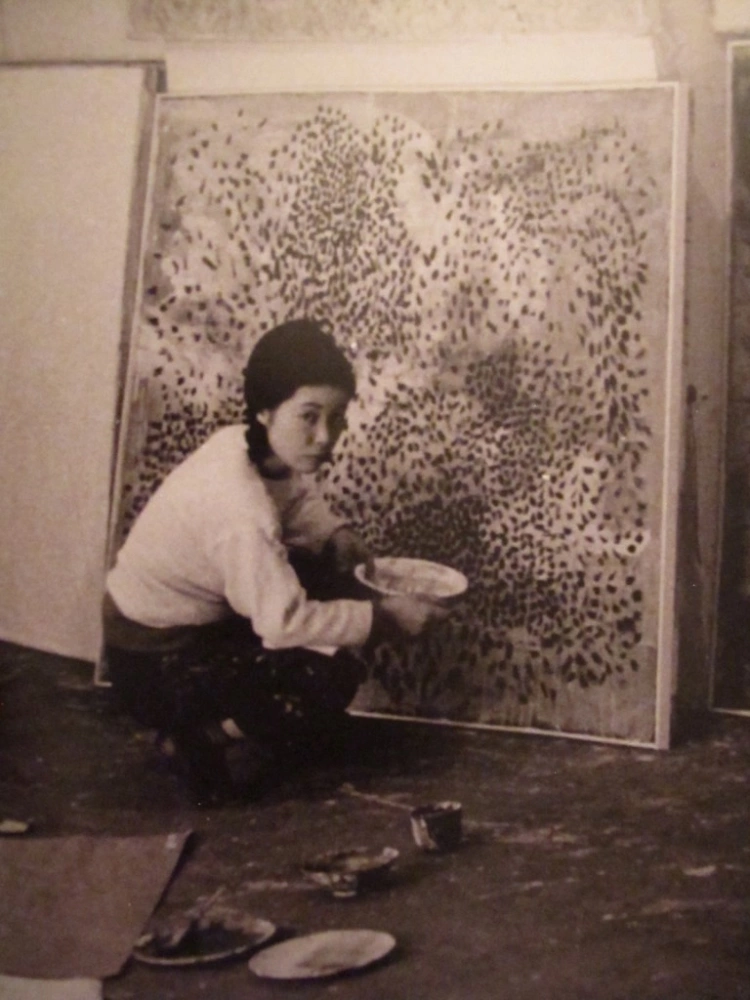

Infinity Net

Her early work in New York included what she called “infinity net” paintings. Those considered of thousands of tiny marks obsessively repeated across large canvases without regard for the edge of the canvas, as if they continued into infinity.

Kusama’s Infinity Net series marks the beginning of a radical shift in her work from the singular abstract, biomorphic forms she painted during her youth to the more obsessive, repetitive works that would define her career.

They also showcase the way she used art to process her mental illness.

No. F. from 1959, is one of Kusama’s first works from the celebrated series. From a distance, the painting looks monochromatic and delicate, but when viewed up close, the complexities of the canvas’s surface become apparent.

The bluish-gray underlay is almost completely obscured by small, white semi-circles, which consume the entire canvas and only allow the gray underlay to be visible in the form of tiny dots.

The organic arched shapes all curve in the same direction, creating an undulating net that would continue on indefinitely if not for the edge of the canvas. This endless repetition caused a kind of dizzy, empty hypnotic feeling; the hypnotic feeling is furthermore translated to the viewer as they are invited to the artist’s mind.

The Nets are both minimal and expressive, bridging the two opposing movements. For Kusama personally, her Infinity Nets have become central to her practice, and continue to influence her work.

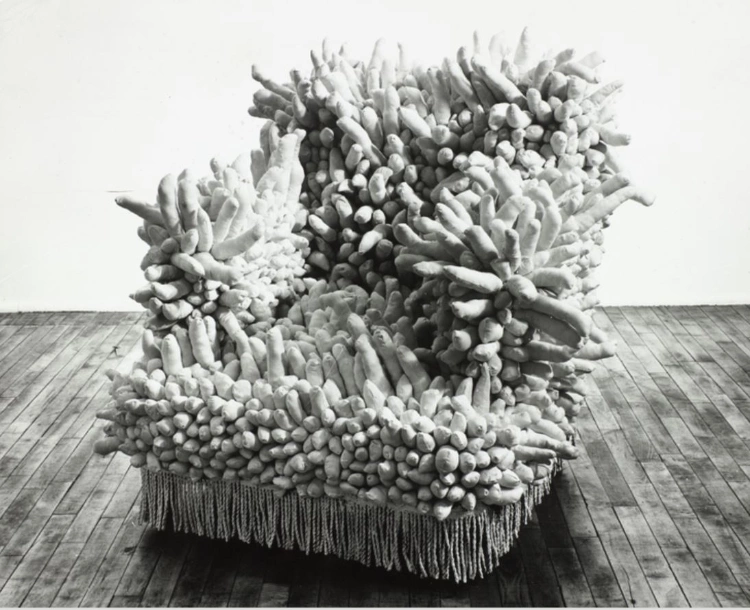

Minimalism / Pop / Avante Guarde

Her paintings from that period anticipated the emerging Minimalist movement, but her work soon transitioned to Pop and Performance art. She became a central figure in the New York avant-garde.

Accumulation No.1, from 1962, is the first in Kusama’s iconic Accumulation series, in which she transforms found furniture into sexualized objects. This piece, consist of a single abandoned armchair painted white and covered with soft, stuffed phallic protrusions, while fringe encircles the base of the sculpture.

No longer limited by the pictorial plane of the two-dimensional canvas, the stuffed sculpture continues Kusama’s repetition compulsion in three-dimensional form. The piece is both humorous and aggressive and works to confront with Kusama’s sexual phobias.

You Know You’re A Great Artist When…

Critics didn’t know what to make of this innovative art, and very soon the struggling artist went from obscurity to notoriety; her fame rivalled that of some of the most famous Pop artists, and Kusama enjoyed the attention.

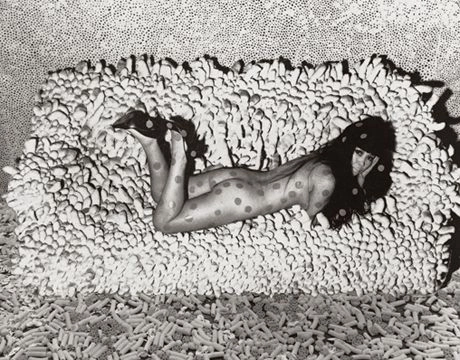

In the Sex Obsessions Food Obsession Macaroni Infinity Nets & Kusama from 1962, she splayed naked on one of her famous soft sculpture furniture pieces laden with phallic accumulations and surrounded with macaroni pasta which forms her familiar pattern of repetition.

By inserting herself into the piece- on top of an object that represents a manifestation of her sexual aversion, Kusama attempts to subvert her own discomfort, in effect, to conquer it. It is a visual juxtaposition of her direct confrontation of a lifelong sexual aversion with the recognition of her nude self as an unmistakable, even if unwilling, object of sexual desire.

Although she is slim and stylish, positioned amongst a groovy psychedelic scene with strong visual impact, the rendering of her signature polka dots across her skin reminds the viewer that she is most comfortable when allowed to be seen as an intrinsic part of the artwork.

This brave presentation of herself in physical dialogue with her fears positions Kusama as a participant in the Feminist art movement of the time and also foreshadows her work in the late 1960’s in which she would use her body and the body of others in public performances.

Happenings

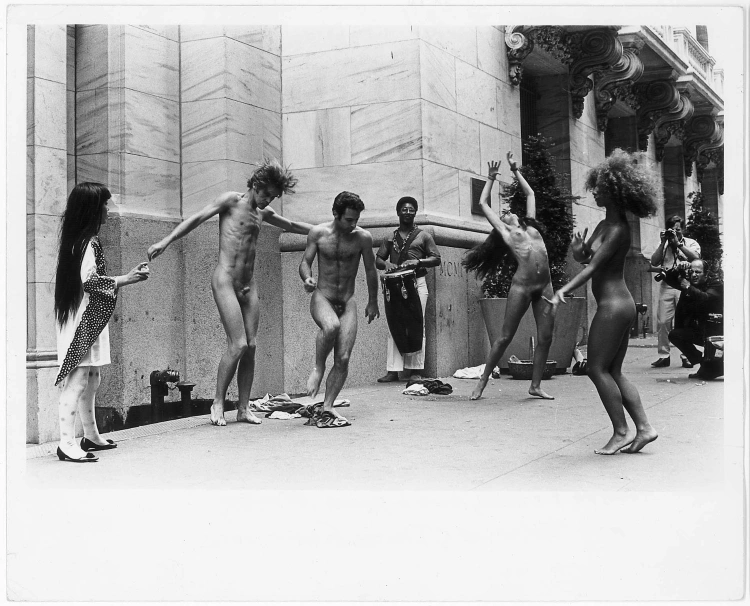

Starting in 1967, Kusama made fewer art objects and began experimenting with the performance art of the moment, ‘’happenings’’. Her first Anatomic Explosion (on the Wall Street) took place on October, 15th, 1968, opposite the New York Stock Exchange.

The performance was in opposition of the Vietnam War and was prefaced by a press release that stated that the money made with this stock is enabling the war to continue. The work featured nude performers dancing to the rhythm of bongo drums, while Kusama painted blue dots on their naked bodies.

For Kusama, nudity represents love and peace and was used to counter the tragedies and horrors of war. After 15 minutes the police came, putting an end to the spectacle.

Growing up in militaristic Japan during the World War II led Kusama to vehemently oppose social injustice and war. Her absurdly theatrical happenings, which were always overly political, were an expression of this opposition.

Mental Exhaustion

Her artistic output during this 15-year period was prolific and diverse, experimenting with various mediums. Sometimes, she would work up to 50 hours without rest. Eventually, the workload coupled with a lack of financial security and Cornell’s death took its toll, and in 1973 she move back to Japan to seek treatment for her mental exhaustion and declining physical health.

She began focusing on her surreal writing and avant-garde clothing line.

In 1977, after being diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive neurosis, Kusama checked herself in to the Seiwa Mental Hospital and has been living and working there by choice ever since.

When Kusama moved back to Japan in the 1970’s, she was all but forgotten by the Western art world. In Japan, she was mostly known for her violence-soaked writings, but that changed in 1993 when she was invited to represent Japan at the 45th Venice Biennale.

Pumpkin

The piece named Pumpkin from 1992 is one of Kusama’s first forays into outdoor sculpture. The giant yellow pumpkin sculpture is painted with rows of black dots fanning out from large to small around the gourd.

The pumpkin’s organic form and grand scale gives the work a cartoonish appearance, highlighting how strange the natural world appears in modern culture. Created in Japan, the work also reflects a shift in Kusama’s practice from her earlier aggressive and politically works to the more kitsch works that consume her art later in life.

The shift can be also attributed to the transition in Japanese culture from rigid and militaristic to a full on embrace of the ridiculous and tacky, as seen in the Hello Kitty cuteness in Kawai culture.

OCD Catharsis

Kusama’s art is fundamentally about obsession and the need, born of anxiety, to repeat certain acts in an attempt to free herself from that obsession. Since childhood, her art-making has been a private atavistic ritual, a necessary inducement to repetition that leads to catharsis.

Obliteration Room ( 2002-present) starts out as a blank canvas. Set up to resemble the interior of a domestic environment, the floor, walls, ceiling, furniture and little knick knacks are all painted sterile white.

Visitors to the room are handed a sheet of round stickers of various shapes and size determinate by Kusama, and invited to affix them to any surface in the room. The interactive installation was the first time Kusama moved away from creating passive environment to creating an environment in which its realization required participation from visitors.

Here’s a video showing Obliteration Room in action:

Hello Capitalism

In 2008, one of Kusama’s Infinity Nets, the same one once owned by Judd, set new art auction price records for a living female artist and led to collaboration with luxury fashion retailers like Louis Vuitton and Marc Jacobs.

Ironically, the woman whose art once protested capitalism and materialism, now fully embraces it.

Kusama began her Infinity Mirror Room series in the 1960’s, and so far has created twenty distinct rooms. They are culmination of her repetitive paintings, soft sculptures and installations into an immersive environment. The piece Infinity Mirrored Room – The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away from 2016, is her most recent iteration.

Each Infinity Mirror Room consists of a dark chamber-like space completely lined in mirrors. This particular room consists of small LED lights hung from the ceiling and flickering in a rhythmic pattern creating pulsing electronic polka dots.

The lights reflect off the mirrors in the intimate room creating the illusion of endless space; only one visitor at a time can experience the installation with the singular visitor becoming integral to the work, as his/or her body activates the environment once in the room.

Kusama’s far-reaching influence can be attributed to the fact that she has always been a step ahead of her time, with her art being at the forefront of many major artistic movements. Yet, her art-making process is so personal, and both a cure and a symptom of her mental illness; it does not fit into any of these defined movements.

Influence

More important than the impact her diverse work has on the art market is its influence on other artists and movements, which spans generations. Her work inspired Feminist artists, Pop artists like Andy Warhol, Performance artists like Yoko Ono, but also contemporary artists like Damien Hirst.

To this day, she represents herself as a lone wolf most comfortable with being known as independently avant-garde; her life is a poignant testament to the healing power of art and the study of human resilience.

Nowadays, Kusama reigns as one of the most unique and famous contemporary female artists, operating from her self-imposed home in a mental hospital.

About David Fox

David Fox is an artist who created davidcharlesfox.com to talk about art and creativity. He loves to write, paint, and take pictures. David is also a big fan of spending time with his family and friends.

Leave a Reply

|

|

|

|

Now get FREE Gifts. Or latest Free phones here.

Disable Ad block to reveal all the secrets. Once done, hit a button below

|

|

|

|