The Cultural Significance of Manga and Anime

by David Fox

Anime and Manga are two different storytelling media. They both originate in Japan, and are closely related, but are ultimately two different things.

Definition of Anime, pronounced AH-knee may, and derived from the English word 'animation' is the term used for cartoons in Japan.

Although profoundly influenced by Western models, including the work of Walt Disney, Japanese animation has developed a distinctive visual style and a range- artistic, dramatic, and in subject matter-unparalleled globally.

The first Japanese cartoons were produced in the early twentieth century, but anime only took off as a creative form after World War II, and especially in the 1960s, when animation became a centerpiece in the young medium of television.

Contents

- What is Manga?

- What's the Difference Between Anime and Manga?

- What Makes Anime and Manga So Popular?

- Why Are Manga Usually Black and White?

- What Are the Origins of Manga?

- Different Styles of Manga

- Global Domination

- Manga Online and Games

- Can Anime and Manga Cause Violent Behavior?

- What Is the Cultural Significance of Manga and Anime in Japan and Other Countries Around the World?

- How Do Manga and Anime Reflect the Values and Concerns of Their Creators and Audiences?

- Recommended Viewing

Today, anime is widely available in Japan on TV, as feature films, and through OVA (original video animation), productions released directly to DVD and on the Internet.

Although often stereotyped abroad as violent and sexually explicit, anime, like manga, is a diverse genre encompassing humorous children's fare, sci-fi robot epics, and thoughtful imaginative creations like the Oscar-winning Spirited Away.

Japanese animation has long been exported, with generations of Americans growing up with various series such as Speed Racer, but only over the past twenty years has anime become an international pop culture phenomenon.

Our today's post is all about Japanese manga and anime. Here is what we are going to cover today:

Plenty of interesting stuff, right!? Stay with us as we plunge into the mysterious world of manga and anime. Let's start with learning a bit more about manga.

What is Manga?

Definition of Manga, pronounced MAHN-guh, is translated in English as 'graphic novels' or 'comics', though such words cannot fully capture the richness and diversity of the genre in Japan.

Manga have a long history and their origins stretch back at least to the Tokugawa period (1600-1868) when illustrated books and the sophisticated graphics of Japan's woodblock prints attracted both elite and mass audiences.

In the twentieth century, mainly after World War II, manga flourished in Japan, drawing inspiration from American comics, like Superman and Blondie, and draining the creative talents of artists like Tezuka Osamu, the famous creator of Astro Boy.

Today, manga are popular among all age groups in Japan, from young schoolgirls to aging corporate executives, and span a remarkable range of subjects, including action, romance, science fiction, sports, erotica, food, and history.

According to some sources, comics make up over forty percent of the books published in Japan and constitute a $4 billion industry, with numerous weekly and monthly magazines catering to the nation's manga-loving public.

Here is one of the largest manga collections to date…

Next, we discuss the difference between anime and manga in Japan.

What's the Difference Between Anime and Manga?

Manga and anime are at the center of significant innovations and cultural debates in Japan.

They are not identical fields-manga can be defined as Japanese comic books, but anime encompasses the breadth of Japanese animation-they have become synonymous with a distinct Japanese contemporary aesthetic and visual culture in the eyes of many media, culture scholars and commentators around the world.

Many consider manga to be the origin: the creative spirit and energy that spawned anime, and later video games and merchandising spin-offs.

In many cases manga defined the template for the key genres-shōjo, shōnen, gekiga and so on-which have come to dominate the wider popular culture of Japan today.

While manga established the roots of this style during the postwar period, it was through anime that a broader global audience became aware of complexity of Japanese visual culture.

Academics and critics have connected anime and manga to various aspects of Japan including motherhood, architecture, social life and customs, gender, homosexuality, popular culture, history and religion.

As Douglas McGray observed: "Japan is reinventing superpower-again. Instead of collapsing beneath its widely reported political and economic misfortunes, Japan's global cultural influence has quietly grown. From pop music to consumer electronics, architecture to fashion, and animation to cuisine, Japan looks more like a cultural superpower today than it did back in the 1980s, when it was economic one''.

Advocates for Japan's recent cultural resurgence point to the concept of 'soft power' in relation to the popularity of Japan's visual culture.

This refers to the possibility of a new cultural renaissance of increased artistic freedom for Japan, and a level of respect, interest and admiration in the culture and history of Japan's visual art both domestically and internationally.

Joseph Nye Jr., who coined the term 'soft power', sees manga and anime as ideal soft power products, claiming they are immediately recognized and widely admired everywhere. He notes the global success of anime such as Pokemon or Hello Kitty, which projects a soft and friendly image that appeals to children all over the world.

Next, we discuss what makes anime and manga so popular among both kids and adults.

What Makes Anime and Manga So Popular?

Anime and manga have long been at the heart of Japanese culture and tradition, with a steady increase of popularity between the generations. Although anime and manga are most popular in Japan, over the last two decades, the popularity for anime and manga has also grown considerably in the USA and all across Europe.

One of the major reasons why anime and manga have stood the test of time and became so popular all over the world is because of their unique ability to grow with their followers.

One of the most famous anime experts, Takamasa Sakurai, claims that Japanese anime has become widely accepted due its unconventional nature. Sakurai claims that „Japanes anime broke the convention that anime is something that only kids would want to watch".

International fans of anime claim that they love the intensity and complexity of the anime story-lines with the endings being incredibly difficult to predict. They also say that they enjoy the fact that anime is often targeted at adult audiences instead at kids.

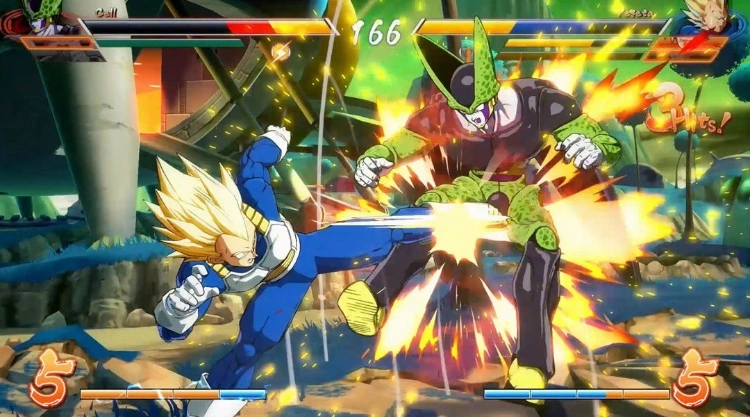

In the UK and USA, many kids watched anime TV series as they were growing up, namely: Dragon Ball Z, Pokemon and Yu Gi Oh. These series have created a soft spot in their hearts for anime.

Nowadays, with the growth of the internet and online streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon, anime has become even more accessible and popular. Now, adults all over the world can relieve their childhoods through more age-appropriate anime series such as Spirited Away and A Place Further than the Universe.

Another reason why anime has become more popular overseas in the last two decades is Japanese shrinking population. Anime producers are now making content more suited to Western tastes, as well as producing anime outside Japan as it is much cheaper. Popular anime producers such as Teyuka now produce and push for their anime to be sold abroad.

Moving on!

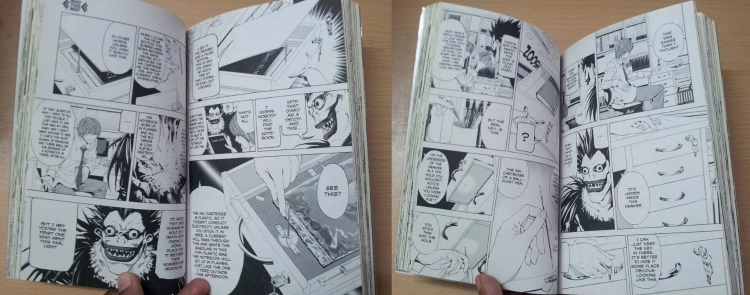

Why Are Manga Usually Black and White?

Have you ever wondered why most of manga are printed in black and white? There can be several different reasons for that, so let's try to mention some of them:

It costs less

This one is pretty much obvious! The black ink costs much less than the color. Just compare the prices for black ink cartridges and color cartridges for your printer too see the difference in price. The lower cost of production results in lower prices for the end product - meaning the readers will be more eager to buy manga.

The Japanese manga magazines are mostly phone book-sized weekly magazines. The producers do their best to keep production costs at a minimum so even elementary schoolkids can buy them without breaking their weekly allowances.

The producers use very cheap recycled paper and only one color of ink. This results in producing some 300-500 pages of manga in less than $5.

It is also important mentioning that manga are usually done by one person. That means for most manga, the artist has to draw and ink almost 50 pages of manga in a month all by himself.

Faster production

Unlike comics in the USA, which generally come out on a monthly basis, a lot of manga comes out weekly. Coloring manga magazines would take a lot of tome and would make it almost impossible to release new chapters in time.

It's a piece of art

Reading through a black and white manga is just as watching a really well done black and white move. It conveys a certain mood, especially in the use of shadows, much better than color could. Over the last few decades manga artists have developed plenty of excellent techniques of using black-and-white art to make their manga unique pieces of art.

Next, we talk about the origins and evolution of manga…

What Are the Origins of Manga?

The term 'manga' can be traced back as far as the 1770's, and has been used to describe the woodblock prints of Katsushika Hokusai.

While the term 'manga' may have been coined in the past it did not gain widespread, favored usage until the 1930's for two reasons.

First, the popularity and national circulation of newspaper modelled on Western layouts brought serialized yankoma manga into home and workplaces throughout Japan.

Second, the growing job market for manga-ka (manga authors) fostered a sustainable manga industry.

Much of the literature on manga is framed by the question of its origin-is it located within Japan's past and therefore a distinctive Japanese aesthetic, or is it a contemporary phenomenon influenced by the West?

Those arguing for manga as a continuation of earlier forms of Japanese graphic and visual art point to stylistic similarities between past and present graphic art, quoting the similar 'dynamic effect' that manga and anime share with narrative picture scrolls (emaki-mono) from the 9th century.

Critics of this continuity express two main concerns with this focus on the past.

Firstly, they claim that it sidelines or ignores the very contemporary nature of this form and the important influence of Western artistic style.

Secondly, they argue that it has less to do with art history and more to do with responding to current political and popular concerns of manga's negative effects on youth and culture-that is, linking manga to the past is a self-justifying argument that hopes to show beyond doubt manga is part of traditional Japanese culture and thus circumvent attempts to censor or ban it as trash culture.

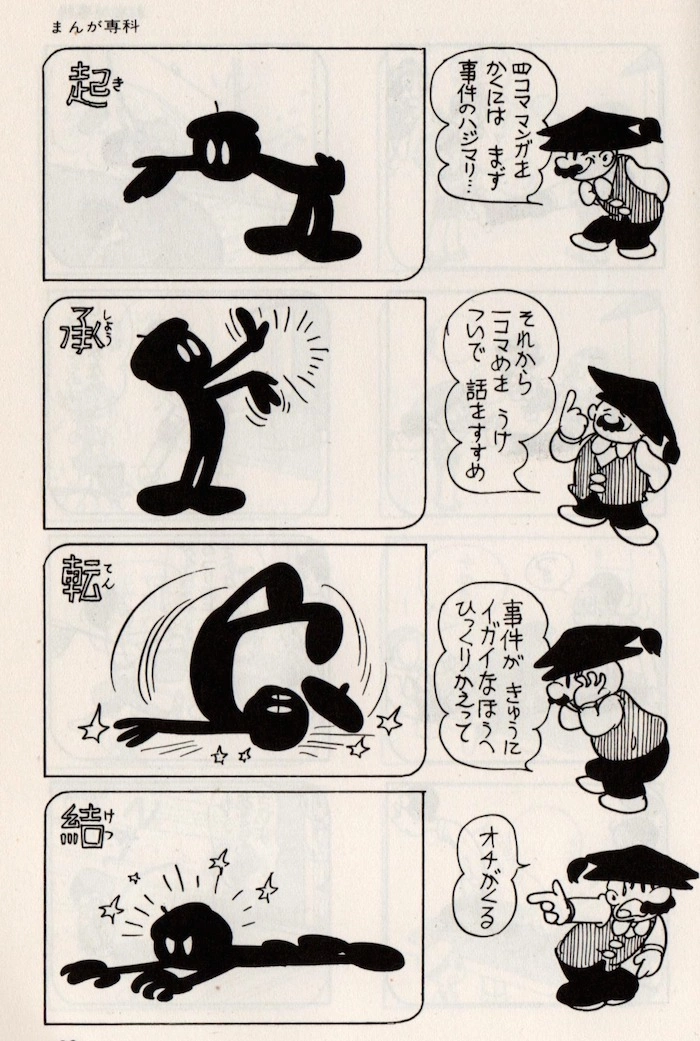

Paving the way for the widespread acceptance of manga in the 1930s was the establishment of two types of comic strips in the 1920s: comic strips for children published in newspapers and journals bought by parents, and short political cartoon strips for adult readers.

This division between mainstream children's manga and political alternative adult manga would remain a lasting feature of the manga industry.

The industry experienced a downturn in the 1930's partly triggered by the changing political environment as increased media regulation and censorship narrowed content to conform to national political objectives.

In the early postwar period, manga succeeded as a form of cheap entertainment for an impoverished, war-weary Japan.

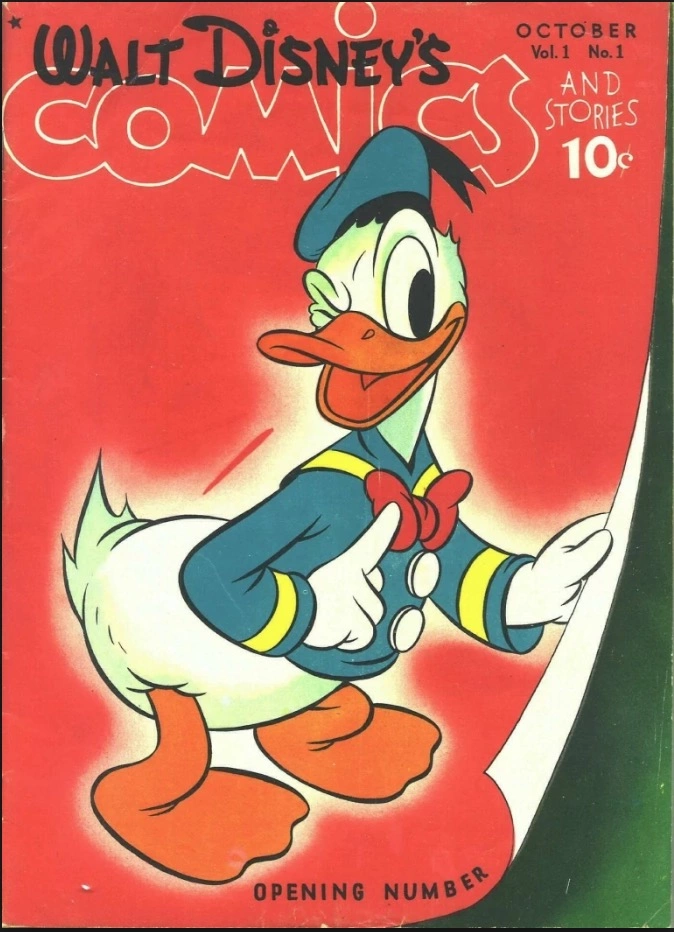

During this time, the development of manga felt the impact of US comics, as Japanese translations of well-known titles such as Popeye, Blondie, Mickey Mouse, Superman, and Donald Duck appeared.

Along with Disney animations, these comics came to have a significant impact on the style of manga created for children.

An important reason for their success was that the Japanese people yearned for the rich American lifestyle that was blessed with various material goods and electronic appliances.

In the early postwar period, manga appeared in three main forms: kamishibai-picture card shows, kashihonya-rental manga and yokabon-manga booklets.

1946-48 saw a boom in storytelling and picture card shows performed in theatres and outdoors throughout Japan.

The picture card shows would use cheaply produce picture cards that the storyteller would speak to, performing a miniature theatre play.

Here is a video showing how a Japanese picture card show works.

Next, we talk about different styles of manga…

Different Styles of Manga

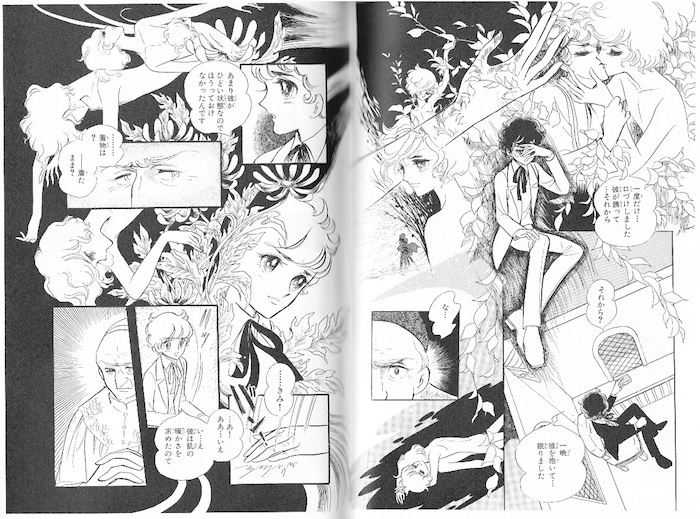

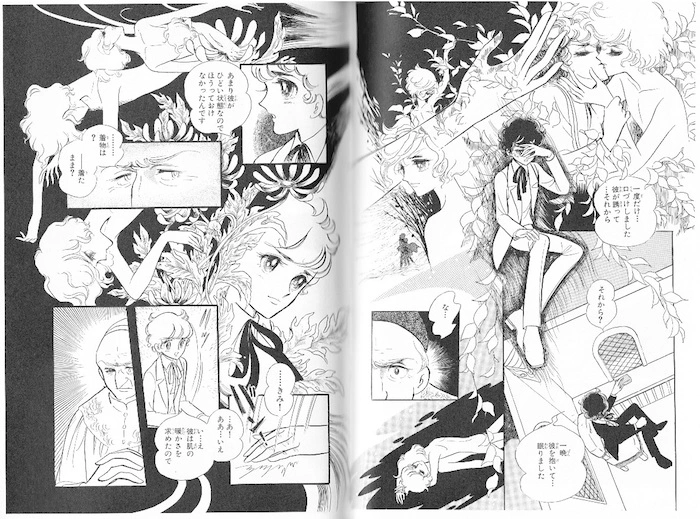

Gekiga

Another factor that supported the growth of the manga industry was the emergence of the book-rental shops. Artists would write manga for magazines or books that could be rented out.

This trend peaked during the mid-1950s as book-rental outlets appeared at train stations and street corners; there were around 30 000 outlets.

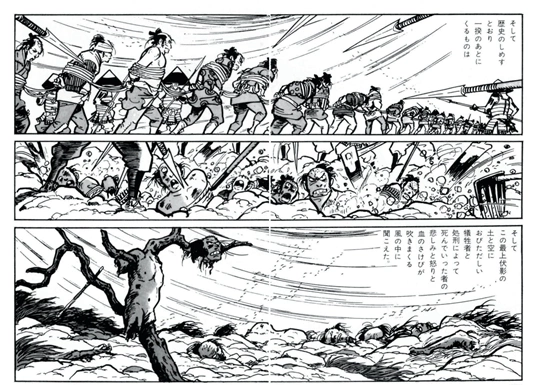

The gekiga (dramatic pictures) style was developed firstly in rental manga.

As opposed to the cuter, anthropomorphic characters that filled many children's manga, the gekiga style contained more mature, serious drama, depicted in a more realistic and graphic style that portrays the tastes of its older readers during the 1950s.

Read: The History of Gekiga

Gekiga's major impact lay not in its graphic style, but in its popularity amongst poorly educated young urban workers and, during the 1960s, university student activities, where it became part of the anti-establishment politics of the time.

In this regard, Sanpei Shirato's Ninja Bugeichō (Secret Martial Arts of the Ninja 1959-1962) was influential.

For many critics this story of peasant uprisings is reflective of student and worker anger over current issues such as the Japan-America Security Treaty.

The third form of manga that flourished in postwar Japan was published in small books (yokabon) sold directly to the public.

They were sold in discount book shops and children's toy shops with deluxe higher-quality manga albums.

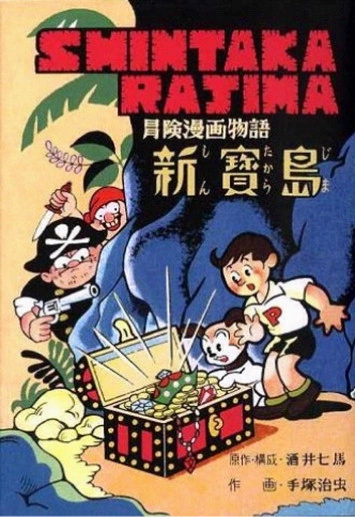

In the Osaka market, small manga books known as akabon( red books), due to the red ink they were printed in, attained wide popularity through the much successful New Treasure Island/Shin Takarajima which sold 400 000 copies from its launch in 1947.

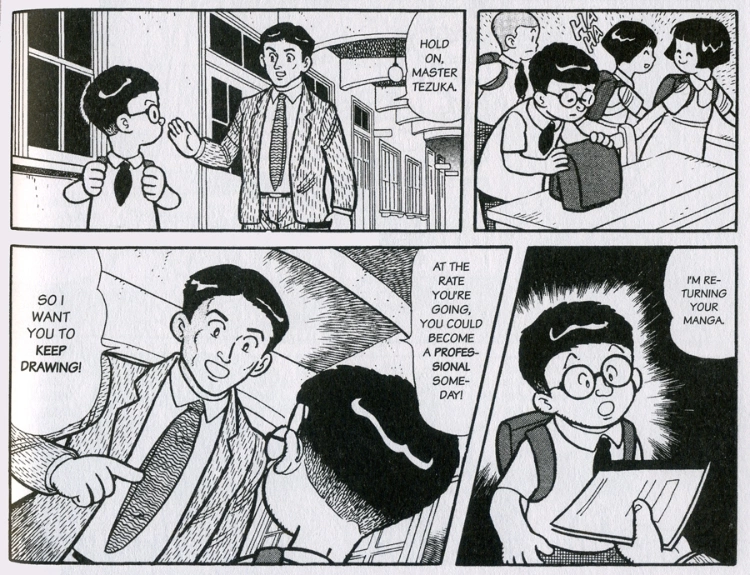

The author of the New Treasure Island, Tezuka Osamu, became one of the most significant figures in manga.

Through the enormous popularity of his work, serialized in children's manga magazines such as Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion, a dominant 'cute' manga style was established.

As opposed to the gritty realism and overt politics of gekiga, Tezuka's manga founded an archetypical manga style featuring cute characters with large saucer eyes.

This style was influenced by Disney animations and comics from United States which had crowded Japan during the Allied Occupation between 1945 and 1951.

Tezuka also incorporated cinematic techniques inspired by German and French movies.

His manga became epic, often spanning thousands of pages, and popularized a longer, serialized form of manga known as 'story manga' which would become a standard format evident in today's manga industry.

Here is a great documentary about Osamu Tezuka we recommend you watch.

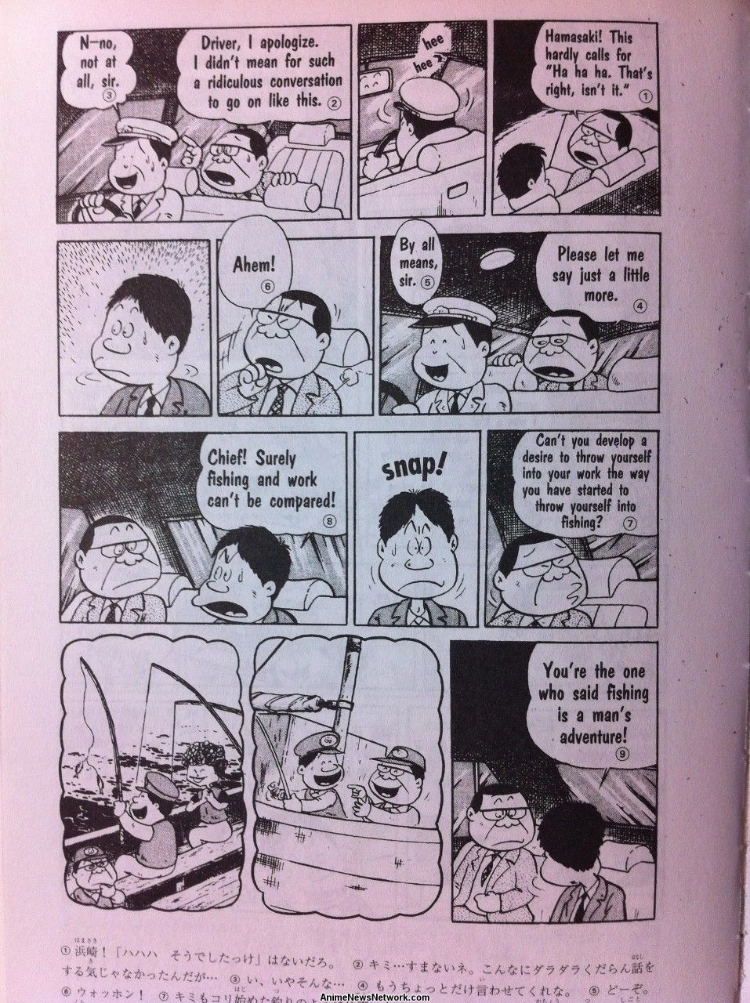

Primarily read by children and regarded as cute, these story manga were an innovative break from the rigid layout and brevity of the 'gag manga' genre and four-panel (yonkoma) comics popular in weekly-magazines and newspapers of that time.

The development of the manga industry from picture card shows to rental manga and to the manga magazine industry is reflected in the employment history of significant manga artists such as Shirato Sanpei and Mizuki Shigeru.

These artists both worked their way up through picture cards, rental manga and then the manga magazine industry during the 1950s and 1960s.

The 1950s established manga as a popular and lucrative element of Japanese entertainment through the success of children's title as Tezuka's Astro Boy and the first weekly comic magazine for boys Kodansha's Shōnen Mangajin (1959).

Astro Boy became typical of the trend for original manga to lead to various spin-offs in other media, becoming one of the first children's TV cartoons in 1963, with various remakes since.

At that time, one of the dominant divisions in the manga market is the split between male and female demographics. Critics have suggested that this division may have become entrenched through the segregated school system in Meiji Japan.

During the 1960s manga broadened its content to include popular genre such as sport. Two important early sports stories that helped establish genre is weekly comic magazines for boys and young adults were the boxing story Ashita no Joe (1968) and the baseball story Kyojin no Hoshi (1966).

Also, the 1960s saw the steady maturing of the manga market and titles which reflected this expansion beyond the children's audience.

Young adults who had read manga as children began demanding more adult and sophisticated material; this included not only stories set in the adult workplace and the world of leisure, but also avant-garde manga such as Garo, an alternative manga magazine (1964-2002).

This magazine serialized the popular peasant revolt story The Legend of Kamui and became an important platform for alternative art manga in Japan.

Moving onto Shojo manga style…

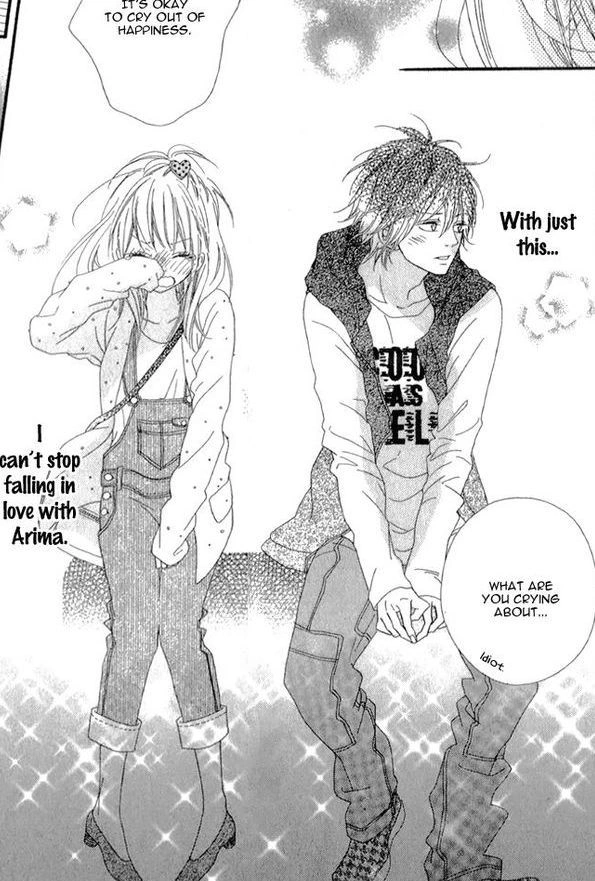

Shōjo

The 1970s were marked by a group of female manga artists who pioneered a new approach to shōjo manga.

Shōjo can be defined as manga aimed at girls less than 18 years of age, but is often more broadly applied to manga aimed at a female readership.

While shōjo includes a variety of genres such as horror, sport, science fiction and historical drama, it is commonly associated with slender elegant male characters and romantic, fantasy based plots.

Some scholars and commentators estimate that today more than half of all Japanese women under the age of 40 and more than three-quarters of teenage girls read manga with some regularity.

While initially dominated by male authors, by the 1970s a group of female artists known as Nijūyonen Gumi /Year Twenty-Four Group pioneered a new approach to shōjo manga introducing new themes and approaches such as homosexual love.

These artists depicted themes such as romantic love between beautiful young boys, for instance, Keiko Takemiya's Kaze to Ki no Uta / The Sound of The Wind and Trees, 1976; while Yumiko Oshima's short manga Tanjō/Birth, 1970, depicted teen pregnancy and abortion.

Moving on!

Tankōbon

During the 1970s, development in manga's layout and composition, graphic style, and gender- specific formats had become firmly established.

A further significant innovation was to occur in the 1970s with the popularization of the tankōbon (paperback) format for manga.

Popular manga previously serialized in weekly and monthly magazines were compiled in a higher-quality paperback more portable for commuters and more attractive for collectors.

The tankōbon soon replaced manga magazines as the main revenue stream for manga publishers.

Let's go back to 1980's and 90's. This is the period when some of the most popular manga and anime had been produced…

1980's and 90's Manga

By the 1980s and 90s manga had become mainstream and were read by nearly everyone of all ages Kyoyo manga (academic or educational manga) is an example of the mainstream appeal of new forms of manga as they were used to inform and educate readers on a range of topics from history and annual festivals to cooking and other DIY (Do It Yourself) areas.

Manga changed again in the 1990s as editors asserted a stronger role in the creative process of manga production.

Some scholars argue that because most editors were more wealthy and educated than artists, adult manga in particular was reformed around their more privileged tastes and interests.

This move away from the working class, artist-created, counter-culture stories of the 1960s and 1970s can be seen in the more factual and niche-interest manga such as the political and economic series Osaka Way of Finance /Niniwa Kin'yudō, and extensively researched nuclear-submarine story Silent Service/Chinmoku no Kantai.

Global Domination

This period also saw the expansion of the global market for manga; manga began to gain a stronger foothold in the United States, long a niche market for Japanese popular culture.

With the release of Akira (1988) and Ghost in the Shell (1995-world-wide release), both based on original manga, Japanese anime and manga began to attract greater international attention than ever before.

These headings were much more 'mature' that the standard animation of the time, and their cyberpunk, dystopian themes came at a time of great interest in the approaching millennium.

In 1988, Ghost in the Shell reached number one on Billboard's video chart in the United States.

By the early 2000s, the manga industry had broadened beyond the familiar Japanese publisher-Kōdansha, Shūeisha, Shōgakukan to include a smaller number of transnational manga distributors and publishers and achieved a globally dispersed audience.

While there are current concerns that the Japanese manga market is becoming stagnant and its fortunes are declining, the circulation of weekly manga magazines have been in steady decline for the last decade-many of the most successful anime, videogames and merchandising lines began as manga.

The enormously successful DragonBall franchise began as a manga series in 1984.

The 2000s have been dominated by the growth of globally effectual brands that exist across various media platforms.

Power Rangers adapted from the live-action Japanese TV show was broadcast in the United States in 1993, and by 2007 it had expanded to 15 television seasons, 14 series and two films.

Its success was overshadowed by the greater popularity of Pokemon, produced by the video game company Nintendo and created by Satoshi Tajiri, which became a successful anime, video game and character-related business franchise.

Shogakkan's Pokemon, the animated version of Nintendo's portable game software was the first huge success by a Japanese anime overseas; its global success has helped establish the abomination of Japan's character-related industry, and has maintained Japan's contribution to the children's entertainment world-wide.

Manga Online and Games

Manga has also moved into online environments offering online manga content and various downloads that extend the audience's access to manga in a more interactive online environment.

This move away from print media to digital formats is extended even further by hand-held video devices such as Nintendo DS and Sony's Play Station Portable which offer a number of titles based upon popular manga or drawing upon the manga style.

Manga's distribution over varied media platforms reveals shifting relationships between the audience and industry in Japan, but also worldwide.

Recently, manga's development has been impacted by the rice of OEL (original English-language) manga, which straddles the Western/Japanese divide.

OEL manga involves taking the 'design engine' of Japanese manga and using it to tell stories created by non-Japanese artists for non-Japanese audiences.

A canonical 'manga style' of cute girls, big eyes, beautiful boys and dynamic action that was used as the engine to create the OEL manga stories and art represents a move to standardize the manga product.

Critics of manga include a range of groups such as parents, women's associations and PTAs concerned over school children reading vulgar and sexually explicit manga and scholars concerned over the sexism and violence directed towards women in manga.

The most extreme critics of manga and anime claim that both mediums can have a negative effect on society, making people more violent and less informed.

There are three broad areas of concern identified. Firstly, too much information, from driving manuals to business information, is being conveyed through manga-a form of caricature that inevitably distorts, simplifies and exaggerates.

These critics note that the depth or complexity or of an issue cannot be conveyed through manga in the same way as prose, poetry or film documentary can facilitate.

Secondly, critics claim that the increasing popularity of manga as an information tool reflects a broader trend in politics, education and religion where the entertainment value of information is highlighted in order to create appeal.

Additionally, further existing concerns that information that is too complex to be compressed into manga will be ignored.

Finally, let us answer one commonly asked question about manga…

Can Anime and Manga Cause Violent Behavior?

A final concern is that sexually explicit and violent manga may cause more violent behavior, especially among younger readers.

This point came to public attention after several sensational 'moral panic' controversial affairs from the late 1980s where manga readers were presented by the media as either threats to social order and stability, or at risk of becoming perverted through their manga consumption.

The case with the highest profile in this regard was the trial of Tsutomu Miazaki in 1989 for the murder of four young girls.

He became known as 'The Otaku Killer'' due to large collection of porn videos, including anime, which police found in his apartment.

While incidents of moral panic generated of concerns over manga's effect on society have achieved great notoriety in Japan, it is usually simplistic and unrealistic to isolate one factor, such as manga, as the sole cause of behavioral problems in an individual.

Other factors may include mental illness, family dysfunction, and poverty or drug addiction while an increasing body of research attempts to broaden the debate beyond an exclusively media- effects framework.

Anime and manga should be understood as exemplar products within Japanese visual culture.

One thing that makes manga culture important in Japan is its penetration into nearly every facet of Japanese life and culture today.

Manga are read in many different private and public settings and consumed by a broad segment of the community. In addition, manga and anime have become increasingly popular around the world.

Networks of Japanese and overseas fans are translating and distributing manga, both commercial and original works.

The manga style provides an engine for various fans to depict their own stories and link to each other through this strange world.

That's all folks! We hope you've enjoyed our post! At the end, we would like to recommend you watching some of the best anime videos we have prepared for you:

Enjoy it!

What Is the Cultural Significance of Manga and Anime in Japan and Other Countries Around the World?

Manga and anime are two of Japan's most popular exports. Manga are comics created in Japan, while anime are Japanese animation films and television shows. Both manga and anime have become extremely popular in other countries around the world, particularly in North America and Europe.

Manga and anime often deal with themes and subjects that are not typically found in Western comic books or cartoons. For example, manga and anime often feature strong female protagonists, as well as homosexual and bisexual characters. This has led to some criticism of manga and anime, with some people claiming that they promote values that are not traditional or "family-friendly."

However, there is also a great deal of support for manga and anime. Many people believe that these forms of entertainment are a positive cultural force, particularly when it comes to promoting acceptance of LGBT people. Many manga and anime fans also see these works as sources of artistic and creative expression that go beyond the simple "good vs. evil" narratives found in many Western comics and cartoons. Overall, the popularity of manga and anime around the world suggests that they are an important representation of Japanese culture, as well as reflecting broader ideas about art, gender roles, sexuality, and so on. Whether you view them favorably or not, there is no denying their significance within Japan and throughout the world.

How Do Manga and Anime Reflect the Values and Concerns of Their Creators and Audiences?

Manga and anime often reflect the values and concerns of their creators and audiences. This is because these media are generally created with a specific audience in mind, and so they tend to cater to the interests of that audience. For example, many manga and anime are targeted at young people, and so they often deal with themes like coming of age, love, and friendship. Additionally, because Japan is such a technologically advanced country, many manga and anime also deal with futuristic themes and settings. In general, then, we can say that manga and anime usually reflect the values and concerns of their target audiences.

Of course, it is important to note that manga and anime are not always aimed at a specific audience. Some manga and anime, for example, may be geared towards general audiences or even adults. Regardless of the target audience, however, we can still say that these forms of media often reflect certain values and concerns. Overall, then, I think it is clear that manga and anime can serve as windows into the values and concerns of their creators and audiences. This is particularly true when one considers how influential these media have become in modern society. They are certainly important cultural artifacts that help us understand our world today! But what do you think? Do you agree with this view?

Recommended Viewing

7 Underrated Studio Ghibli Films

Top 10 Goriest Anime from before the Year 2000

Another Top 10 Most Popular Anime on the Planet

Top 10 Adult Anime

About David Fox

David Fox is an artist who created davidcharlesfox.com to talk about art and creativity. He loves to write, paint, and take pictures. David is also a big fan of spending time with his family and friends.

Leave a Reply

|

|

|

|

Now get FREE Gifts. Or latest Free phones here.

Disable Ad block to reveal all the secrets. Once done, hit a button below

|

|

|

|